|

|

Clothing in the Viking Age

As with many aspects of Viking-age material culture, our knowledge of Viking-era clothing is fragmentary. The Viking people left few images and little in the way of written descriptions of their garments. Archaeological evidence is limited and spotty. Thus, different scholars examining the evidence come to different conclusions. What is presented in this article represents only a range of possible interpretations.

|

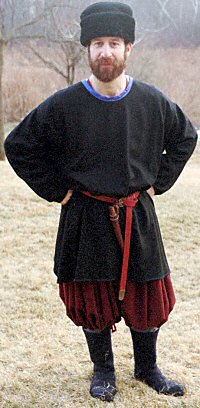

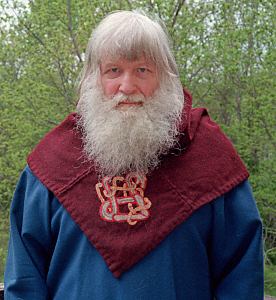

All the Germanic peoples in northern Europe wore similar clothing. While variations did exist, throughout the Viking era and across the Viking lands, clothing styles were remarkably consistent. The photo on the left shows men's clothing similar to that worn throughout the Norse regions, while the photo on the right shows a distinctly eastern Norse style for men. Up top, men wore a tunic that was tight fitting across the chest with a broad skirt. Down below were trousers which could be either loose fitting or tight. Women wore a long shift with a suspended overdress. Both men and women wore a long cloak or a jacket to provide warmth and protection in inclement weather. Most of our knowledge of Viking-era clothing and textiles comes from archaeological finds, while some comes from literary sources and written law. Most finds of Viking-era fabric are from grave goods. As one might expect, fabric doesn't survive very well when buried underground. The survival of large quantities of fabric is quite rare and requires unusual soil conditions. Sometimes the traces of textiles are found on the underside of jewelry, as the corrosion products of the fabric in contact with the jewelry in the grave etch the jewelry. From these ghost images, the weave and thread count may be determined. |

|

Remains of clothing are also found in other places. Norse people used worn out clothing for many purposes. Sometimes, it was coated with pitch and used to seal cracks in the shipbuilding process. In other cases, fabric was coated with pitch to use as a torch, but never lit. These pitch-coated fabrics have survived very well. At least one entire garment (a pair of men's trousers) has survived from the Viking era because someone used it in the process of building a ship.

|

The outer garment for the man's upper body was the kyrtill, the overtunic. It was constructed from wool and was constructed using surprisingly complicated patterns, with many pieces that needed to be cut out of the fabric and sewn back together. However, when it was all laid out, very little fabric went to waste. |

|

The photo to the left shows the individual pieces of fabric being fitted together to make the tunic. The photo to the right shows a finished tunic. The complexity results in a garment that doesn't bind or restrict movement. The upper part of the garment is relatively tight-fitting, but the sleeves are fitted to provide freedom of motion. The skirt ranged from thigh length to knee length. As with most articles of clothing, the length was determined by the wealth of the owner. A poorer man would not waste material that wasn't needed, while a more wealthy man would show off his wealth by using more material than was needed. On hot days, the skirt was lifted up and tucked into the belt for better cooling. Sleeves were probably longer than is typical in modern garments, reaching well past the wrists. |

|

|

The tunic was pulled on over the head. There were usually no fasteners, although some tunics had a simple button and loop of thread (left) to fasten the neck opening. A keyhole neckline was the most common, although many other shapes were used for the neck opening for both men and women. Men's necklines were high, since a garment that revealed the chest was considered effeminate. Tunics of all but the poorest people were decorated with braid, at least on the neckline and cuffs. The tunics of the more wealthy were also decorated with braid on the hem of the skirt. The braid was woven from brightly colored wool using the tablet weaving technique, described later in this article. |

| Silk was also used to trim a tunic, although the cost of imported silk must have limited this kind of trim to only the wealthiest people. The 10th century sample shown to the right is silk trim, embroidered with silver thread. When new, the silk was probably dyed a brilliant red color. |

|

|

Under the tunic, it's likely that most men also wore an undertunic (left). This was made most commonly from linen. (Linen was more expensive than wool, but more comfortable against the skin.) The construction was similar to that of the overtunic, except that the sleeves and skirt were made longer. It has been suggested that the undertunic was visible extending past the overtunic, so that people could see that one was wealthy enough to be able to afford an undertunic. |

|

The linen undertunic found at Viborg is one of the few linen garments that has survived reasonably intact. A modern replica is shown left and right. The front and back of the body of the garment is made with two layers of linen, sewn together in an elaborate pattern with a square in the center and with diagonal stitching out to the seams, shown to the left. This replica (and the original) also have a square neck opening with overlapping flaps in front to seal out cold weather. The flaps are held shut with cords and loops (right). |

|

|

It appears that a wide range of styles of trousers were used in the Norse lands. Some were tight. Some were baggy. Some trousers were of simple construction. Some were complicated, using elaborate gores around the crotch area for freedom of motion, and built-in socks (like modern sleepwear for toddlers), with belt loops around the waist. A sketch of a historical pair of trousers with this pattern is shown to the left. In chapter 16 of Fljótsdæla saga, the trousers of Ketill Þriðrandason are described as having no feet, but straps under the heels, like stirrups. Trousers had no pockets and no fly. The lack of a fly meant that men had to pull up their tunic skirts and drop their trousers to relieve themselves. The lack of pockets in any Viking-era clothing meant that men and women had to carry their everyday items in other ways, described in more detail later in this article: suspended from the belt, carried in pouches, carried around the neck, or suspended from brooches.

|

|

|

It is possible that some trousers were held up with a simple drawstring in the waist band, as seen in the reproduction trousers shown to the left. Yet many surviving examples of trousers have belt loops, suggesting that the trousers were held up with a belt. Some means of holding up the trousers is required. Since there is no fly or opening at the waist, the waist band must be big enough to pass over the hips. A pair of trousers with no means to secure them will simply fall down to the ankles. Fighting men took advantage of that fact. In chapter 6 of Bárđar saga Snćfellsáss, Lón-Einarr was fighting with Einarr when Lón-Einar's trouser belt snapped. As Lón-Einarr clutched at his trousers, Einarr gave him his death blow. |

One episode in the sagas suggests that tight-fitting clothing was considered showy or ostentatious. In chapter 45 of Eyrbyggja saga, Ţóroddur Ţorbrandsson had been wounded in a fight. His trousers (which had feet in them) were soaked with blood. A servant tried to remove the trousers, tugging with all his might, but the trousers would not come off. The servant said that the Ţorbrandsson brothers must be stylish dressers, since their clothes were so tight fitting that they couldn't be taken off. Subsequently, Snorri gođi looked more closely and discovered that the pants were pinned in place by a spear in Ţórodd's leg.

|

One wonders if Ţórodd's trousers were similar to the Thorsbjerg trousers, a tight fitting style. The original is a well-preserved artifact from 4th century Germany, but poorly preserved trousers with a similar cut were found in Viking era Hedeby. A sketch of the pattern is shown to the right, and a linen reproduction is shown to the left. The original had belt loops on the waistband, and feet attached to the legs, which were not reproduced here. Detailed information, sewing instructions, and patterns for this reproduction may be downloaded from the Hurstwic library. |

|

|

Some of the Germanic people (such as the Saxons and the Franks) are known to have worn puttee-like leg wrappings from knee to foot (shown in many of the photos on this page, and to the left) to gather the excess fabric of their baggy trousers. The evidence for their use in western Norse lands is scant, but better evidence exists from eastern Norse regions. |

|

The wraps consistent of two long, narrow strips of cloth, typically wool, which were wound around the leg and foot. By starting at the knee and wrapping downwards and ending at the toes, no clips or fasteners are needed. The wraps stay firmly in place, even during vigorous activity. During the Viking age, the fabric would have been woven to the correct dimensions for the intended purpose, rather than cut from larger piece of cloth, as was done for the replica shown to the right. As a result, a leg wrap from the Viking age would have selvages along each edge which resisted fraying, rather than a stitch used on the modern replica. |

|

|

An episode in the sagas suggests that leg wrappings were uncommon enough in Iceland to be worthy of note. Chapter 9 of Gull-Ţoris saga describes Grímr, who wore a white cloak, white trousers, and swathing bands (spjarrar) wrapped around his legs. And so, he was called Vafspjarra-Grímr (swathing band Grímr). On the other hand, these leg wrappings provide significant protection to the lower leg when crashing through dense brush, such as exists in Icelandic birch forests. In addition, they help keep legs and trousers warm and dry when walking in snow (left). |

|

We know little about underpants used during the Norse era. No surviving examples are known to exist. It is believed that they followed the same patterns as trousers but were typically knee length. Like trousers, some may have been simple, and some may have been complicated in the crotch area, again for freedom of motion. Like trousers, they had no fly. A drawstring at the waist or belt held the underpants up, and they may have had drawstrings at the knees. When available, they were made of linen for comfort, but wool was used as well. In chapter 16 of Fljótsdæla saga, the saga author mentions that at the time of the events in the saga (10th century), men did not wear underpants. Yet, just two chapters later, Gunnar Þiðrandabani is described leaving his tent at night to relieve himself wearing nothing but tunic and underpants. (At that moment, his pursuers spotted him, and Gunnar spent the rest of the night and the following day dressed so while eluding his pursuers across the cold Icelandic landscape.) |

|

Gísla saga Súrssonar (ch.16) says that Gísli walked one night to the neighboring farm at Sćból dressed in shirt and linen underdrawers, with a cloak over his back. Gísli's plan was to enter the sleeping longhouse at night to kill his brother-in-law Ţorgrímr. Although not explicitly stated, the lack of trousers would make it difficult for the people of Sćból to recognize the intruder by touch in the dark longhouse.

These two episodes (and many others) suggest that linen underwear was worn to bed.

It's been suggested that very poor men did not use underclothing and thus may have slept naked. In chapter 18 of Ljósvetninga saga, Ţorbjörn rindill, a poor man from the East Fjords, was hired by Guđmundr inn ríki (the powerful) to serve as a spy at the home of Ţorkell hákr (bully). On the night of the attack, Ţorbjörn heard the dog barking and men riding up to the house. He sprang from his bed and ran outside naked, with his clothes in his hand and got dressed outside. The episode suggests he slept naked.

|

The cloak was simply a large rectangular piece of wool, sometimes lined with contrasting color wool. Cloaks provided protection from the cold, from the wind, and to a limited degree, from the rain. Some cloaks were made with very dense, very thick wool, which would have provided extra protection. Cloaks were typically worn offset, with the right arm (the weapon arm) unencumbered by the cloak. I had long wondered if overlapping the cloak over the right arm, rather than in the middle, would really matter. During a recent snowstorm, I had an opportunity to put it to the test. Grabbing for something in a hurry (in this case, a projectile in flight) was substantially easier with the cloak offset. When overlapped in the middle, the cloak always got in the way. Cloaks could be embroidered, or trimmed with tablet woven braid. Typically they hung to somewhere between the knee and the ankle depending on the wealth of the owner. The sagas tell of much longer cloaks, called a slæður, so long that it trails on the ground. Egill received one as a gift from his friend Arinbjörn (Egils saga, ch. 68), made of silk, embroidered with gold, with gold buttons down the front. When Egils son later wore it without permission, and returned it with the hem all dirty, Egill was extremely displeased. As is described below, women sometimes wore clothing that dragged on the ground. When Flosi was given a long slæður as part of a legal settlement (Brennu-Njáls saga, ch. 123), he thought the long garment was an insult, suggesting he was a woman. |

|

During the Norse era, Iceland exported wool in the form of homespun cloth (vaðmál) or ready-made cloaks (vararfeldur), also called a shaggy cloak (röggvarafeldur). There were strict regulations on homespun, and it was used as a standard exchange product, in the same manner as silver.

|

Homespun cloaks had a shaggy exterior, like sheepskin. One explanation is that the shaggy appearance was created by tying additional threads to the warp threads while the fabric was being woven (left). |

|

An explanation that better fits the descriptions of the fabric in the stories is that tufts from the fleece of the sheep were looped around warp threads but not pulled tight, leaving a large loop. The resulting garment resembled a patchy lamb fleece. A modern reconstruction of a shaggy coat displayed on a mannequin is shown to the right, but it's worth noting that this reproduction differs in appearance from surviving fragments of historical shaggy fabrics, shown left. Perhaps the technique used in making the reproduction is in error, or perhaps the surviving fragments have changed their appearance over the intervening centuries. |

|

|

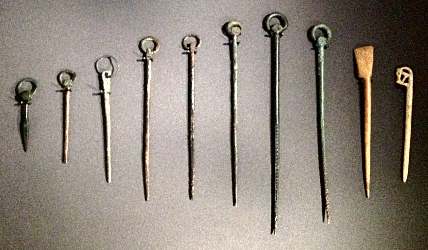

Cloaks were held in place by a pin at the right shoulder. The pins ranged from simple bone pins to elaborate gold jewelry. A common style was the penannular brooch (right top). The pin is held captive on a ring that has a break in it to allow the pin to pass through the ring after it has been passed through the fabric. Like all Norse jewelry, the brooch typically would have been highly decorated. A modern replica simple pin fastener is also shown to the right, and an assortment of historical pins are shown to the left, made from iron, bronze, wood, or antler. |

|

|

Other outer garments were also used, including woolen coats and jackets. Much of the evidence for this kind of outer garment comes from East Norse lands. A reproduction of an exceptionally fine woolen coat is shown to the left. It uses a complicated pattern, and is lined with wool and trimmed with fur. |

|

Caps were made of wool, or sheepskin, or leather and fur. Some had ear flaps for warmth. Typically, they were made in the Phrygian style, with four or more triangular pieces sewn together. A modern replica cap made in this manner is shown to the left, and some stitching details of the cap are shown to the right. |

|

|

Grágás, the medieval Icelandic lawbook, has further evidence on the nature of caps worn. The law [St 362] prohibited a person from pulling the hat off of someone else's head. If there was no chinstrap, the penalty was a fine. If there was a chinstrap and the hat was pulled forward, the penalty was lesser outlawry (banishment). But if there was a chinstrap and the hat was pulled backwards, the hat wearer had the right to kill in retaliation, since it was considered throttling. |

|

Other hood-like head coverings called höttr were worn, especially for protection in foul weather. Presumably, the höttr covered the head and shoulders, like hoods worn in the later medieval period. In Fljótsdćla saga, Sveinungr ordered a young boy at his farm to head out and gather in the sheep. The boy wanted to get his hood and gloves before leaving, but Sveinungr shamed him into leaving immediately. Sveinungr wanted the boy to be spotted and mistaken for Gunnarr, who was being pursued and who had been taken into Sveinung's protection. The replica hood shown to the right uses an extremely simple pattern, in which all the pieces of fabric are rectangles. A drawstring helped close the hood around the face. Other hoods are more carefully fitted to keep out weather. |

|

|

And it seems likely that some hoods were decorated. The replica hood shown to the left is decorated with embroidery (right) in the Urnes style using a design found on a silver broach from Iceland. |

|

The sagas also tell of prestigious hats, such as Russian hats (gerzkr hattr). In Laxdćla saga (ch. 12), the slave merchant Gilli inn gerzki (the Russian) was wearing such a hat and other fine clothes. It is possible that silk-trimmed hats found in some Birka graves represent this kind of hat.

|

Socks apparently were optional, depending on the wealth of the individual (although more on that in a moment). Those without the means for socks probably used moss or grasses or even hay to line their shoes. When socks were available, they were made of undyed wool. A sock found in York has a band of red trim at the top, which is how the reproduction shown to the right is constructed. |

|

|

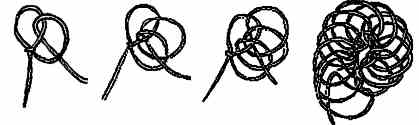

However, Norse socks were not knitted (which apparently was unknown to the Norse). Instead, they were made using an ancient technique called nálbinding (needle-binding). Using a single large, thick needle, it was a method of knotting the yarn. Although time consuming, this approach resulted in a nearly indestructible garment. If the thread were to break or wear out, the garment would still be intact, since the thread was everywhere knotted to neighboring threads. Mittens and caps were also made using this technique. The sketch to the left shows the steps involved in making an article of clothing using the nálbinding technique. Note that the fabric grows in a spiral pattern. Once the spiral is large enough, it is knotted back on itself to create the shape of the finished article. |

|

I met two Icelandic women who showed me that my original understanding of the nálbinding technique was faulty. It may be conceptually complicated, but they demonstrated to me that knotting together garments was not only simple, but extremely fast. The cap shown to the right was the work of a single afternoon. A number of different "stiches" were used in the Viking era. To the left are shown details of two different nálbinding stitches. |

|

| Mittens were also made using nálbinding techniques. A historical Viking-age mitten made using nálbinding is shown to the right. In addition, there are examples of mittens made by sewing together pieces of woven woolen fabric. |

|

|

|

|

A cross-section of a turnshoe-style shoe is shown to the right. The heavier sole is sewn to the lighter uppers, then turned inside out to put the stiching on the inside. One might think that having the seam on the inside would be uncomfortable, but it's not. The seam is out of the way, and it doesn't touch the foot. Viking-age shoes probably didn't last long - perhaps a few months to half a year before they wore out and were replaced. As a result, worn-out shoes are common finds in Viking-era trash pits. The replica shoes shown to the right are reaching the end of their useful life, based on the visible wear in the sole. |

|

|

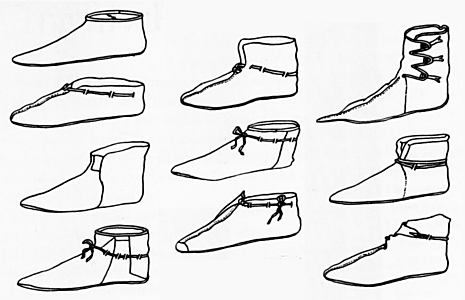

In some regions, leather survives well, and complete examples of a number of different shoe styles have been found. The illustration to the right shows various shoe styles found at the Viking-age trading town of Hedeby. The shoe shown to the left was found in the Oseberg ship burial. |

|

|

The shoes shown to the left are a copy of a pair found in York in England. They are a bit more elaborate than some, and use toggles, rather than laces, for closing the shoe. Two toggles are shown to the right, the top one fastened, and the bottom one loose. The shoe toggles are easily adjustable, so that one can adjust the snugness of the shoe as the leather stretches. |

|

|

The top of the York shoe is "whipped" with a contrasting color thread, both as decoration and to reinforce the edge (right). The sole extends well up the back of the heel, perhaps to provide some additional life to the shoes by keeping the heel seam up off the ground where it can't be scuffed. The shoe shown to the left is a copy of one found in Hedeby. The seam that joins the upper is in the center, rather than on the side, as with the York shoe, above. This pattern is much simpler to construct. |

|

|

Most shoes were ankle height, although a few examples of higher boots have been found. A pair of calf-high reproduction boots are shown to the right, which use the same kind of toggle closure as the shoe shown above. A similar pair is shown to the left, with decorative stitching on the back. The saga literature also mentions high shoes. In chapter 9 of Hávarđar saga Ísfirđing, Valbrand's sons took off their high shoes while they raked hay. However, the use of this kind of boot among the Norse people has been contested. The surviving examples typically are from market towns, where Norse traders met people from around the world. These examples may have been brought to these towns by traders from other regions. |

|

|

A find from Coppergate in York suggests that, in at least some cases, the shoe toggles were to the inside of the feet, rather than to the outside as in all the reproduction shoes shown above. The reproduction shoes shown to the left were made using this alternate pattern. I can certainly see how they'd be a lot easier to fasten in that location. |

Shoe fastenings occasionally broke in use. Skarpheđinn Njálsson's shoe lace (skóţvengr) broke as he ran towards an ambush, forcing him to stop and retie it, as described in chapter 92 of Brennu-Njáls saga. It didn't slow him down any. He leapt onto the ice and slid across the frozen river to kill Ţráinn.

|

Shoe laces were routed through the upper of the shoe to avoid putting pressure on sensitive areas of the foot. As a result, the lace ran below the ankle bone on the sides, and above the heel in the back. |

|

However they were fastened, shoes occasionally came off, according to the sagas. Chapter 19 of Svarfdćla saga tells of a battle in which Ögmund's shoes had come off in the deep snow. Karl offered to stand in front of him for protection while Ögmundr put them back on.

|

|

|

Viking-era belts were leather, and considerably narrower than belts later came to be. Surviving buckles and strap ends tell us that 2cm (3/4 inch) was about the widest belt commonly used. There were no belt loops in a tunic, so any excess length was knotted around the belt and allowed to hang freely. The free end was weighted with a decorative strap end. Not only was the strap end decorated, so were the buckle and the belt itself. Modern replicas of a belt buckle, decorative plates, and a strap end are shown to the right. Two essential items worn on the belt were a utility knife and a pouch of soft leather or fabric. Since garments had no pockets, people needed some place to store the items they routinely carried with them, such as coins, a scrap of clean cloth (to wipe one's hands and face), a fire starting kit, etc. Keys, however, were routinely carried around the neck. Smaller weapons, such as a sax, might also be worn on the belt. |

|

The sagas suggest that other forms of clothing were worn in the Viking age, some of which are poorly understood. Kjalnesinga saga describes Kolfiđ's clothing in chapter 7 as being baggy trousers, a hooded cloak fastened between his legs, and furry calfskin shoes. People thought his appearance was ludicrous.

|

The working clothes of a farmhand are described in chapter 16 of Fljótsdćla saga. The man wore a gray tunic, with the flaps fastened up on his shoulders and the loops hanging down at his sides. Over that, he wore a white work shirt. The details of these garments are obscure (in both the Icelandic original and in English translation), but it is possible the man's tunic was a blađakyrtill, with a skirt made of two flaps slit at the sides. Perhaps it resembled the tunic shown to the right. |

|

|

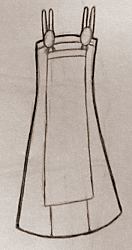

In general, women's clothing was made from the same materials as men's clothing. Typically, a woman wore an ankle length linen under-dress or shift, with the neck closed by a brooch. Over it, she wore a shorter length woolen dress suspended by shoulder straps fastened by brooches. This kind of suspended dress is sometimes called a hangerock or an apron-skirt. The details of how these garments were constructed is speculative. Some interpret the outer dress as two separate panels, others as a slightly flaring tube-shaped dress, longer at the back than the front. There is also evidence for an overdress similar to the one worn by the woman on the right, completely covering the shoulders and requiring no brooches to hold it in place. |

|

|

The rear straps of the suspended dress were long enough to pass over the shoulder to the brooches, while the front straps were much shorter, as seen in the photograph to the left. A pin and catch on the inside of the brooch held the loops of the straps to the brooch. |

|

Some grave finds suggest multiple layers of fabric inside surviving brooches. It has been suggested that a fabric panel was hung by loops from the brooches over the suspended dress, along the lines of an apron. One can only speculate whether the panel was intended to help keep the suspended dress clean, or was decorative, or perhaps both. It has also been suggested that the panels of the suspended dress were not fully sewn, allowing the dress to be opened to allow for nursing, and that this additional panel was used to cover the opening. |

|

|

Several different styles of Viking-age brooches are shown to the left. In modern times, these brooches are sometimes called turtle brooches, since their shape is similar to the shell of a turtle. A modern replica is shown to the right. |

|

|

Frequently, glass or amber beads, or other jewelry was strung between the brooches. A 10th century example from Sweden is shown to the left. Women also carried needed items (e.g., keys, scissors, needles, a knife, and a whetstone) suspended by cords or chains from their brooches, or from their belts. |

|

|

Some examples of Viking-age glass beads are shown to the left, and a historical string of glass beads from the Viking age is shown to the right. |

|

|

The woman shown standing in the doorway above to the right is wearing an ankle length coat-like outer garment over her suspended dress, but cloaks or shawls were also used and were probably more common. One such coat was found in Birka with a neckline cut so full that the oval brooches underneath were visible when the coat was closed and fastened. A modern replica is shown to the left. Women often used tri-lobed brooches (right) to fasten the neck opening of their clothing. |

|

|

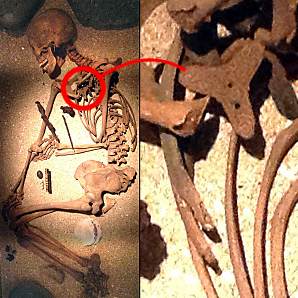

These skeletal remains of a Viking-age woman clearly show her tri-lobed brooch in place where it fastened the neck opening of her burial clothes. Belt buckles or other fastenings are rarely found in women's graves, as they are in men's graves, suggesting that women's belts were woven fabric, rather than leather. Alternatively, it is possible that women did not routinely wear belts, as men did, and instead, they carried all of their everyday items suspended from their brooches. |

|

|

Head coverings were typically worn by women, perhaps as simple as a knotted kerchief over the head (left), which was suggested by finds at the Oseberg ship burial. Rígsţula (verse 2) says that even women of the lowest class wore a headdress. A number of different kinds of head-coverings for women are mentioned in the sagas, some of which are elaborate headdresses, which may have been worn like jewelry on special occasions. Laxdćla saga (chapter 45) tells of a headdress given by Kjartan to his bride Hrefna as a wedding gift. It had eight ounces of gold woven into the fabric. It has been suggested that the type of headdress worn served to distinguish married from unmarried women. |

Women's shoes were similar to men's shoes in virtually every particular.

|

Some evidence suggests that women's clothing was worn long. Images of women in picture stones and jewelry (right) show long, trailing skirts on female figures. Saga evidence also suggests long clothing for women. Perhaps the best evidence comes from Gísla saga (ch.34). As Gísli’s wife and foster-daughter walked with him, their long clothing left a track in the frost which Gísli's enemies were able to follow directly to his hideout. |

|

A moment's reflection suggests that long, flowing clothing was impractical in the agricultural society of the Viking age. Trailing garments would get soiled while working around animals and would be awkward around the fire burning on the floor of every longhouse. Perhaps high status women wore such long clothing on special occasions. As is often the case with Viking material culture, we are reminded of the limits of the available evidence.

Children's Clothing

|

There is little surviving evidence to help us determine what sort of clothing children wore, but there is little to suggest that children's clothing was anything other than adult clothing cut to fit the child's smaller frame. |

|

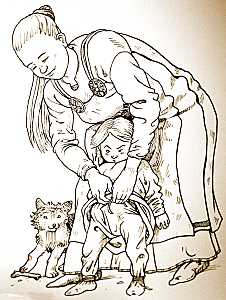

|

Tunic and trousers were probably typical for boys, and a dress for girls. Fljótsdćla saga (chapter 11) describes the everyday clothing worn by Helgi and Grímr, boys twelve and ten years old. Their tunics were plain striped rough homespun wool, with trousers below. They both wore cloaks over their tunics. |

|

|

To the left is shown a replica of a boy's tunic and shoes, and to the right, boy's trousers. The garments follow the same patterns as adult clothing, but are cut to fit a child. |

|

Slaves' Clothing

We know little about the clothing worn by slaves, or how it differed from the clothing worn by free people. Most likely, it was similar to but simpler in design and execution than clothing worn by free men and women. Coarser, undyed fabric was probably used to reduce costs, with little or no ornamentation.

One of the few descriptions of slaves' clothing in the sagas appears in chapter 12 of Laxdćla saga. Höskuldr entered the booth of a merchant looking to purchase a concubine (ambatt) and his eye was drawn to Melkorka, who was poorly dressed (illa klćdd). After purchasing her, Höskuldr dressed her in fine clothes which suited her better.

All of the steps of making a set of clothing, from processing the fibers, to spinning, weaving, cutting, and sewing, were done by the women of the family. Since the process was so labor intensive, a set of clothing was highly prized and carefully maintained. And since the work was skilled, the women doing this work were an indispensible part of the household.

Clothing was commonly made from wool or linen. Other fabrics (such as silk) were known, but were costly and rare. It has been thought that outer garments were typically wool, while under garments were linen. More recent research suggests that linen was commonly used for outer garments as well.

|

Both fabrics begin with natural fibers. Wool is made from the fibers from the coats of sheep. Sheep were raised throughout all of the Norse lands, not only for wool, but for food as well. |

|

|

Fleece that had been shorn or plucked from sheep was cleaned (left) to eliminate dirt and debris and combed with iron toothed combs (right) to smooth and disentangle the fibers, making them easier to spin. |

|

|

Linen is made from fibers in the stem of the flax plant, a slender, erect plant that grows about 100cm (40in) tall. Earlier references suggest that flax grew only in the most southerly of the Norse lands during the Viking age. However, more recent evidence suggests that flax was cultivated in the more northerly lands, including northern districts of Norway and Sweden. Both pollen samples and placename evidence in Iceland suggests flax cultivation there, as well, although it seems unlikely that flax would flourish there. Linakradalur (flax field valley) is shown to the right as it appears today |

|

|

Flax was harvested before the seeds ripened. The seedpods were removed, and the stems were "retted" in shallow water, a process that caused the plant to decompose and loosen the fibers without causing the fibers to rot. The process creates very disagreeable odors. |

|

Linen fiber was mechanically separated from flax stems by beating the stems, using a wooden beating tool such as the one shown to the right. The fibers were then combed to separate out any woody particles from the linen fibers and to align the fibers to make the spinning process easier. |

|

|

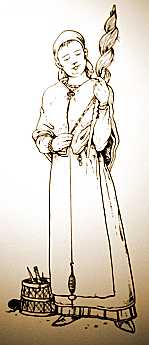

The bundle of wool (or linen) fibers was attached to a simple distaff, which the spinster could secure to her belt or under her arm. The spindle (in the upper left in the photo to the right) was weighted by a spindle whorl, a small stone with a hole cut in the center (right). The spindle was set spinning and allowed to sink towards the floor. Fibers were teased out of the mass of raw material on the distaff and spun together between the fingers to create thread. Spindle whorls are common archaeological finds. The examples in the photo on the right are from the collection of the Icelandic National Museum. The finding of a spindle whorl and a bone needle at the L'Anse aux Meadows site is convincing evidence that women were present at the site during the Norse era. Different sized spindle whorls were used for making different weight threads. Some spindle whorl finds are so small that they were originally classified as beads for jewelry. Only recently have they been reclassified as whorls for making extremely fine thread. Making the thread was probably the most time-consuming aspect of clothing manufacturing. It is estimated that about 35 hours of labor was required to make the thread required for one day of weaving. |

|

|

The spindle whorl shown to the left was found under the streets of modern-day Reykjavík in a very early house site from the 9th century. The runic inscription says, “Vilborg owns me.” The historical records list no Vilborg at this location. Perhaps she was a servant? A guest? Regardless, the find suggests this spinner was literate in the runes. |

|

Finished thread was wound onto a thread reel, shown to the left. Alternatively, thread was wound onto animal bones. A skein of dyed thread, ready for the loom, is shown to the right. |

|

|

The dyeing process could be applied to the fleece, to the thread, or to the finished fabric. The dyes available to Norse weavers were limited, but many of them were bright. A variety of vegetable dyes were commonly used, resulting in a range of colors: browns, from off-white to beige through russet to dark brown; reds, from a pale red to a deep red; yellows, from pale to a brilliant gold; and blue. The results of some modern dyeing experiments are shown in the photos. The yarns shown to the right were dyed with natural dyestuffs found in Iceland, as was the tunic and tablet-woven trim shown to the left. |

|

|

The sagas mention that dyestuffs were collected. Svarfdćla saga (ch.18) says that Ţórhildr sent her sons, Ţorleifr and Óláfr up on Klaufabrekka (right, as it appears today) to bring back some herbs for dyeing (litgrös, literally color-grasses). |

|

The Icelandic sagas often mentions clothing color. Brightly colored clothing was a symbol of wealth and power, no doubt due to the additional expense of the dye stuffs and the multiple dyeing operations required to make bright colors. The wearing of black (blár) clothing is a frequent literary convention in the sagas, indicating that the wearer is about to kill someone.

|

In the old language, blár probably meant a dark blue-black, and the sagas distinguished the color blár from the color svartr. Blár is the color of a raven, whereas svartr is the color of a black horse. In modern Icelandic, blár has taken the meaning blue. Presumably, a true black could not be obtained with dyes of the time, and a dark blue-black was as close as could be obtained. The deep black of the tunic of the eastern Norseman in the photo at the top of this article would have been very difficult to obtain during the Norse era. It has been suggested that using dark-blue dyes on the wool from a "black" sheep (which were more a dark brown than true black) resulted in blár-colored clothing. |

|

|

Frequently, linen undergarments were left undyed, in part because linen is difficult to dye. The looms used by Viking-age weavers would have allowed them to make a wide variety of plaids, checks, stripes, and other patterns, but for whatever reason, they chose not to. Few examples of these patterened fabrics are found in the archaeological record. When patterns were woven in to the fabric, Viking weavers more commonly used fine patterns, with one or two threads of a single contrasting color thread closely spaced in the weave, illustrated in the sketch to the left. Patterned fabrics are mentioned in the sagas. For example, when Skarphéđinn visited the gođar at Alţing with his father and brothers, he is said to have worn black-striped (blárendur) trousers (Njáls saga, ch.120). |

|

Fabric was woven on a vertical loom. A vertical loom is little more than a wooden framework that leans against the wall. It stands about head-high, which puts the working area at a convenient height for someone standing in front of the loom. The modern reproduction shown to the left is a bit more narrow than the more typical width or the replica loom shown to the right. Typical looms from the period were about 2m (80in) wide, capable of weaving material as wide as 165cm (65in). |

|

|

The warp threads were tensioned by means of the stones tied to the threads at the bottom. The warp threads were moved relative to one another using the heddle rods (the horizontal rods located halfway down the loom). |

|

|

Each warp thread had a loop of thread around it tied to one of several heddle rods. Thus, by moving the heddle rods forwards and backwards relative to the warp, a shed was created through which the weft thread was passed on a shuttle. |

|

The arrangement of the warp threads on the heddle rod and the movement of the heddle rods between each pass of the shuttle allowed a variety of weaves to be created, including plain weave (left) and twills of various kinds (right). |

|

|

|

After each pass of the weft thread, a wooden beater (shown at the top of the photo to the left, along with thread and shuttles) was used to push the new weft against the fabric above. Finished material was wound up on the top beam, using the handle on the right side of the beam (barely visible in the loom photo to the right). Other materials were used as beaters, including broken sword components. The historical beater shown in the bottom photo to the left is a broken portion of a pattern-welded sword blade, fitted with a wooden hilt, having a wooden crossguard and pommel. Weaving using a vertical loom is described as being both tedious and physically demanding, requiring that the weaver walk back and forth from one end of the loom to the other with each pass of the shuttle. However, vertical looms allowed a woman to weave cloth of any required width, from wide to narrow. Thus, it was not necessary to waste cloth by weaving material wider than needed. It is estimated that in one day, a weaver could produce one ell (50cm, about 20 inches) of two ell wide fabric (1m, about 40in): one half of a square yard per day of work. |

|

|

Because of the cost of making fabric, clothing patterns were very efficient in their use of fabric. The material was cut with little loss or waste of precious fabric. The top sketch to the right shows the pieces making up a simple woman's underdress, and the bottom sketch shows how they were cut from a single piece of fabric as it came off the loom. The yellow is the body of the garment, the magenta are the sleeves, the light blue are the underarm gussets, and the green are the gores for the body. The only wasted fabric was the white neck opening. There is little information about what sort of templates (if any) were used, and how they were laid out on the fabric to ensure the pieces were cut accurately.

|

|

|

The fabric was cut with iron shears (left). Generally, this tool appears to have been carried by women in a leather case suspended from their shoulder brooches (right). |

|

|

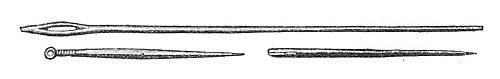

Garments were sewn together using needles made of bone, wood, antler, or metal. Larger needles were typically made from organic materials, but smaller needles (similar in size to those used today for hand stitching) were made of iron or copper alloy. The small size of the needles and of their eyes suggest that fine thread was used for stitching, consistent with some of the fine weaves found in finished fabric from the Viking age. |

|

Needles were often stored in needle cases made of bone, iron, or copper alloy. These cases are common finds in the graves of women, and were suspended from the brooches worn by women. When hanging, the case kept the needles safe and secure (left), yet it was easily opened to reveal the needles inside when needed (right). |

|

|

As with weaving, sewing the clothes was a time-consuming, labor-intensive task. The seams in this replica women's underdress took about 25 hours to sew by hand. The seamstress estimated that she could sew the seams at a rate of about 1m per hour (about 1 yard/hour). Again, there is little information about how (if at all) the fabric was held in position as it was sewn by a Viking-age seamstress. |

|

|

A variety of seams and stitches were used, including the finish stitch shown to the left. Some of the seams were finished on both sides, so that it is nearly impossible to tell the outside from the inside of the garment from looking at the seam (right). |

|

|

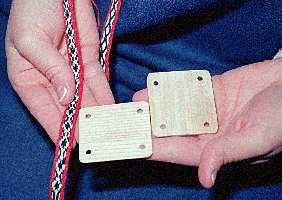

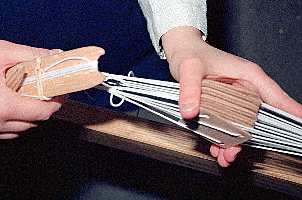

Decorative trims and braids (such as used around the neck opening of a tunic) were made using a process called tablet weaving. In tablet weaving, a large number of various colored warp threads were threaded between tablets made of wood, bone or heavy leather (left). |

|

|

As the tablets were rotated, different colored threads were brought to the top of the shed. The weft thread was passed through the shed on a shuttle. |

|

|

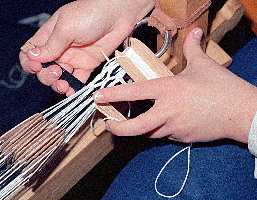

With each pass of the shuttle through the shed, a beater was used to tightly pack the threads (left). By rotating the tablets in a systematic way, a decorative colored pattern was created in the material (right). |

|

|

The warp threads were tensioned between the weaver's belt and some heavy, immovable object such as a wall or pillar. |

|

|

The photo to the left shows how typical tablet woven braid used dozens of tablets to create very elaborate patterns. Some modern samples of tablet woven braid are shown to the right, above, as it is woven, and below, sewn to the sleeve of a tunic. |

|

Another method of weaving braid is inkle weaving. While the use of inkle weaving is known over a broad period in history, its use in the Viking era is debatable. Archaeological evidence is sparse. Inkle weaving can not produce as many pattern variations as tablet weaving, but it is much faster.

|

Drawstrings (for the waistbands of trousers, for example) were made by finger braiding, in which loops of yarn were moved from finger to finger to create braid. Modern practitioners do it at lightning speed, turning out large quantities of braid in a short time. Presumably Viking-age women were no less speedy. |

|

|

Embroidery was also used to decorate clothing. The modern reproductions of a cap (left) and a hood (right) are decorated with embroidery around the edge. |

|

Wool and linen were the most commonly used fabrics. There are also examples of fine silk, which must have been imported from Asia, although only the very wealthiest people could have afforded it. Leather was used where appropriate, for shoes and occasionally for outer garments.

|

Furs and animal skins were used for warmth on winter garments. Chapter 22 of Fóstbrćđra saga states that the Greenlander Lođinn wore a sealskin coat and trousers, while chapter 8 of Bárđar saga Snćfellsás says that Ingjaldr was accustomed to having a great fur cloak over him when on board his ship. During the Viking age, there was extensive trade in furs. Traces of marten, beaver, bear, fox, and squirrel pelts have been found at the trading town of Birka. The sketch to the left shows marten and sable hunting and was taken from Olaus Magnus' History of the Northern People published in 1555. Some furs were worn as status symbols. A bear skin might be worn by someone courageous enough to have attacked and killed a bear. |

Norse era garments were probably finer, better proportioned, better designed, more brightly colored, and better suited to their purpose than one might ordinarily imagine. The materials that have survived (both the fabric itself, and the stitching) are much finer than one might expect given their time in history. Samples of fabric with over 125 threads per inch (60 threads per cm) have been found. Hand stitching finer than modern machine stitching seems to have been the norm. Norse people probably expected their clothing to last for years without much attention. Unlike moderns who have a different set of clothes for every day of the week, Norse people probably had a single set that was expected to last for years.

The value of a set of clothing can be put into perspective by considering the number of hours of labor required to raise the sheep, shear the sheep, card the wool, spin the thread, weave the fabric, cut the fabric, and sew the garments, all of which was done by hand labor. Clothing was desirable booty in a Viking raid (along with precious metals and weapons), further emphasizing the value of clothing in the Viking era.

The production of cloth for everyday use was a home craft. Professional clothmaking probably did not occur in Viking lands, although professionally made cloth was imported from other lands during the Viking era.

Besides its obvious utilitarian functions, clothing played other roles in Norse society. Clothing could be a love token, either premarital or extramarital. In chapter 17 of Kormáks saga, Ţorvaldur asked for and received the hand of Steingerđur, who had been romantically involved with Kormákur. When Kormákur later asked Steingerđur to make him a shirt, she refused.

Then, there are the curious episodes in the sagas in which women sew up men's sleeves. In chapter 17 of Grettis saga, it is said that the ship captain's wife made a habit of sewing up Grettir's sleeves for him. It's been suggested that this was done every day, so that the wide, buttonless sleeves of the tunic could be made tight at the wrists for maximum warmth and freedom to work. I remain unconvinced of this interpretation, yet it suggests the importance and value of fashionable clothing to the people of the Viking-age.

|

Clothing was a sign of hospitality. Any family which could afford spare clothing would certainly keep warm, dry clothing on hand for travelers. In the wet, cold Northern climates, few things would be more welcome to an arriving traveler than a set of dry clothing. Clothing from the Viking era appears to have been utilitarian, comfortable, and practical. It's surprisingly warm, but adjusts for varying temperature ranges. Actual clothing from the period was, like other Norse craft items, both finely made and highly decorated. |

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |