|

|

Viking-Age Laws and Legal Procedures

Laws and legal procedures varied from one Norse land to another and

changed and evolved throughout the Norse period. We probably know more about law

in Iceland during this period than other lands because more was written about it.

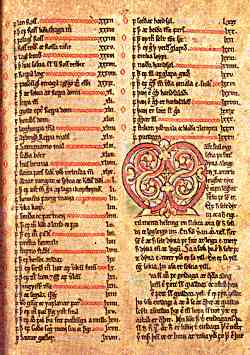

Icelandic law

books, such as Grįgįs (right), were written hundreds of years after the

Norse era, but many of the laws and legal traditions described in the book date

from the earlier commonwealth era. The laws were first written down in the winter

of 1117-1118, and at least some of the laws in Grįgįs are thought to represent

the law as practiced at that time, shortly after the close of the Viking age.

Laws and legal procedures varied from one Norse land to another and

changed and evolved throughout the Norse period. We probably know more about law

in Iceland during this period than other lands because more was written about it.

Icelandic law

books, such as Grįgįs (right), were written hundreds of years after the

Norse era, but many of the laws and legal traditions described in the book date

from the earlier commonwealth era. The laws were first written down in the winter

of 1117-1118, and at least some of the laws in Grįgįs are thought to represent

the law as practiced at that time, shortly after the close of the Viking age.

In addition, many of the Icelandic family sagas provide extensive details of laws and legal procedures as central parts of their plots. Again, these were not written down until hundreds of years after the events described, but they do provide a valuable, if distorted, picture of legal procedures of the era.

Rather than outlining all the variations in law throughout the Viking age, this article focuses on the law and legal procedures as they are believed to have existed in Iceland in the middle of the 10th century. During the 10th century, Icelanders created and then fine-tuned a unique form of government, unprecedented in European history. The Icelandic settlers were opposed to a central state dependent on the authority of a lord or king. Writing in the 11th century, Adam of Bremen said of the Icelanders, "they have no king except the law."

A system of laws was set up whereby people were governed by consensus and where disputes were resolved through negotiation and compromise. That is not to say that violence was not employed. Feuds and violence were permissible and even required in order to maintain one's honor in some instances. But adherence to the law was highly regarded, as observed by Njįll in chapter 70 of Brennu-Njįls saga: "With law our land shall rise, but it will perish with lawlessness."

Throughout the Norse world, open-air governmental assemblies called žing (things) met regularly, usually once a year in most of the Norse lands. Local žing, regional žing, and (in the case of Iceland) a national žing existed, called the Alžing. These meetings were open to virtually all free men. At these sessions, complaints were heard, decisions were rendered, and laws were passed.

|

|

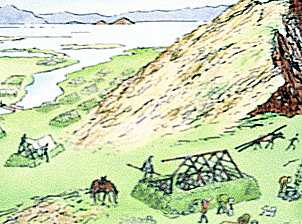

For centuries, Iceland's Alþing met every summer at Þingvellir (Assembly Plain), a magnificent rift valley shown to the left. This site is spectacular not only for its historical significance, but also for its beauty. It's dotted with canyons, caves, rivers, springs, waterfalls, and lakes. |

|

|

The river Öxarį flows through the valley, which is immediately adjacent to Þingvallavatn, Iceland's largest lake. The Alþing met for the first time in the year 930, making it Europe's oldest national assembly. |

|

By the end of the settlement era, Iceland was divided into four administrative regions, called quarters (fjórðungar). In each quarter were nine chieftains, called goði (plural goðar). (In the middle of the 10th century, three more goðar were added to the North Quarter.) A goði was a local chieftain with specific legal and administrative responsibilities.

The goði was the "first among equals". The original goðar were probably the leaders of the ships carrying settlers to Iceland, and who claimed the land and divided it up among their followers. Originally, the goði may have had a special relationship with the gods, and he probably was responsible for the pagan religious rites for his followers. After the conversion to Christianity, little changed. The gošar maintained a special relationship with the new church, and the secular responsibilities remained intact. The office of goði (called the goðorð) was normally hereditary, but the goðorð could be transferred between individuals. Additionally, the gošorš could be shared among men, so there might be more than thirty-nine gošar. However, only one goši from each gošorš could participate in the official business at the Alžing.

The gošorš had no fixed boundaries. Allegiance to the goði from the people was voluntary. A free man could chose to support any goði in his district. A man could change support from one goši to another with only minor formalities. The allegiance was a two way street: the goði looked after the interests of his men, and the men provided armed support in feuds and other disputes.

|

The goðar met in regional þing in the spring, called vįržing. Each vįržing was presided over by three gošar, and all the supporters of each goði (called þingmenn) were required to attend. Ruins from the regional žing site at Hvįlseyraržing at Dżrafjöršur in west Iceland are shown to the left. At these regional þing meetings, regional disputes were tried and settled. |

The Alþing was the national equivalent, meeting for two weeks at the end of June every year. All thirty-nine goðar attended, each accompanied by at least two advisors. The goðar were required to attend. Any free man could choose to attend, but each goði required that one out of every nine of his supporters accompany him to the Alþing. Þingmenn who did not attend were required to pay a tax to the goði. These funds helped offset travel expenses for those who did attend.

In order to be legally fit to attend the þing, a man had to be "able to ride a full-day's journey, and bring in his own hobbled horse after baiting, and find his way by himself where the route is known to him" (Grįgįs K89).

A goði who was involved in a feud or contentious litigation often brought much larger followings in order to back up his discussions with lethal force, if needed. In chapter 14 of Hęnsna-Žóris saga, it is said that Tungu-Oddr rode with 300 men to Alþing. The goði was expected to argue the cases of men from his region at the Alþing. In return, the goði called upon his men for their armed support in feuds with other goðar.

The Alþing provided a place for men from all over the country to meet, to discuss issues, and to settle grievances. Three legal functions were performed at the Alþing: the laws were recited by the law speaker; the laws were made by the law council; and the laws were judged by the quarter courts.

The law council (lögretta), consisting of the goðar and their advisors, chose a law speaker (lögsögumaður) who was responsible for the preservation and clarification of the legal tradition. In the years before a written culture developed in Iceland, the law-speaker literally spoke the law, reciting out loud one third of the laws at each annual meeting of the Alþing. Thus, over the course of his three year term, the law speaker would have recited the entire law code. The written law code (Grįgįs) contains oaths and other formulae composed with rhythmic elements and alliterative patterns, making the laws easier to remember when the laws existed only in oral form. The law speaker was the only official who received a regular payment.

|

|

The focal point of the Þingvellir is a small hill with grassy slopes and a rock outcropping called the Law Rock (Lögberg). Today, it's marked by the Icelandic flag. While standing on the Lögberg, the law-speaker recited the laws. Public speeches and announcements were also made here. The rock cliff behind the speaker directed his voice, allowing him to be heard by all. (A recent informal re-enactment showed that, indeed, the voice of a powerful speaker could be clearly heard across the valley.) Each goði (or one of his advisors) was required to attend the recitation of the laws. Other interested parties could also attend and participate in the ensuing discussion. |

|

The painting to the right shows Collingwood's 19th century interpretation of the Alþing in session. The lawspeaker stands on the Lögberg (in the center of the sketch) and recites the laws, while goðar and other interested parties listen. In the foreground are booths (bśðir), temporary stone structures covered with a tent-like tarp that served as both dwellings and meeting places while the Alþing was in session. The law speaker could exert influence, but did not "rule" the country. The power remained in the hands of the goðar. Instead, the law speaker was the repository of legal knowledge in the era before the laws were written down. He was consulted on any disputed points of law. He had a seat at Lögberg and directed the activities there. |

|

The law-council (Lögretta) was the legislative body of the Alþing. The voting members were the goðar. They reviewed and amended existing laws, made new laws, and granted exemptions from the law. They also had the power to make treaties in the few cases that Iceland had dealings with foreign lands.

|

|

The exact site at Þingvellir where the law council met is not known. Grįgįs (K 117) states only that the council meets where they have long met. A probable site is directly east of the Lögberg in a region now flooded by the river. |

|

Based on the description in Grįgįs, it's likely that the court sat on three concentric rings of wooden benches, with the goðar in the middle row, each with one advisor sitting in front and one behind. The law speaker presided over sessions of the law council. A re-interpretation of earlier field studies suggests a different location for the meeting place of the Lögretta, at least during the heathen period prior to the conversion. On Spöngin, a rocky area between two deep water-filled ravines, three concentric circles of turf were identified. Perhaps they are the ruins of the three rings of benches used by the law council. |

|

The four Quarter Courts (fjórðungsdómur) tried cases against individuals at the Alþing. The Quarter Courts were comprised of 36 judges, nominated and controlled by the goði from each quarter. Grįgįs (K20) says that in order to qualify as a judge, a man must be free, with a settled home, capable of taking responsibility for what he says, and older than twelve years old.

The decisions of the judges needed to be near-unanimous, causing frequent deadlocks. (If six or more out of the thirty-six judges disagreed, then the case was deadlocked.) This problem was solved in the 11th century by adding a Fifth Court, an appeals court, in which decisions needed only to be majority.

The courts were not at all like what one thinks of as a modern western court of law. There were no public prosecutors. All cases were private suits. Usually, cases were prosecuted by someone close to the injured party, such as a family member, or a goði. But an individual could bring action in a case even if he were not involved in the case. A man might choose to do so because he could acquire wealth and fame by the successful prosecution of a case. If no one wanted to take a case, violations of the law might go unprosecuted.

The regulations governing the court were complicated and were aimed at ensuring in every possible way that there could be no doubt about the justice of the outcome. Judges, witnesses and litigants all had to take solemn oaths. Witnesses could testify only to what they saw and heard themselves. Witnesses swore oaths not only about the activities surrounding the original offense, but also about legal procedures that had been followed as the case progressed. Thus, for example, summons witnesses swore that a person was correctly summoned to the court.

(It's worth pointing out that the swearing of these oaths probably precluded Christians from participating in court cases until Iceland adopted Christianity in the year 1000. A Christian would probably be disinclined to swear an oath on a blood-reddened ring, an act that was required in order to participate in court cases. However, few people were probably effected. Evidence from Landnįmabók suggests that from the time that the Alþing was established until Christianity was adopted, "Iceland was completely pagan." Icelandic law and the heathen religion were tightly connected during this time, as evidenced by the fact that the leaders of the religion and the leaders of the government were one and the same: the goðar.)

The penalty for perjury was severe and swift, both by law and by custom. When it was found that Eysteinn had perjured himself in court, men refused to support him, as told in chapter 3 of Reykdęla saga og Vķgu-Skśtu. Įskell rode away with his men to execute Eysteinn for his crime, but before they could arrive, Eysteinn burned everything of value on his farm to prevent it from being confiscated: his house, livestock, and even his household. Then, he fled the country.

The author of Laxdęla saga says that men whose testimony was doubted could clear themselves by suffering an ordeal, described in chapter 18. The author adds that heathen men undergoing an ordeal were just as conscious of their responsibility as Christian men. The ordeal involved raising an arch of turf cut from the earth. A man who passed under the arch without it collapsing was thought to be free of guilt.

Cases might not necessarily be decided on testimony, but on the correctness of the legal procedure being followed. If one side followed the correct procedure and the other did not, the first side won the case, regardless of the facts of the matter. The final portion of Brennu-Njáls saga is a virtual trial transcript, replete with claims and counter-claims of incorrect procedures. In addition, external force could be brought to bear to influence the court's decision. The sagas tell of bribes, of threats of violence, and of actual violence in court.

| An example occurs in chapter 24 of Vķga-Glśms saga. Žórarinn prepared a

case against Glśmur at the Hegranessžing. (Booth ruins at the site are shown in

the photo to the right.) When the word was sent that Glśmur should come to

court to defend himself, he found his way blocked by a solid mass of

armed men, with room for only one man at a time to pass through to the court.

Glśmur thought it inadvisable to pass into that pen. (The word is kvķ, an enclosed pen where livestock are milked, and Glśmur didn't want that kind of milking.) Instead, he formed his men into a wedge formation, spears pointing forward, with himself in the fore. In a single rush, they made their way to court. Because of the dense crowd, it wasn't until late in the day that Glśm's enemies were able to drive him away from court. When the court was convened a second time. Glśmur pointed out that the sun had touched the horizon and thus the case against him had lapsed and was void. |

|

The courts were only one of several ways that disputes could be settled. Arbitration was a less formal process, in which both parties allowed neutral third parties to investigate and decide the case. Or, one party in a dispute might offer self-judgment, allowing the other party to decide the terms of the settlement. This approach was used when the first party felt that the second party would act with moderation, or if the first party was so weak that he was in no position to negotiate terms. Lastly, the parties might resort to bloodshed, either in formal duels, or in blood feuds (discussed in more detail in the article about honor).

It is important to note that during the Norse era, only two of the three branches of modern government existed. The Alþing provided the judicial functions through the Quarter Courts and the legislative functions through the Law Council. But no executive functions were provided. Once the court had decided that someone was guilty of breaking the law, the Alþing had no power to execute a sentence. That was up to the injured party, or his or her family or supporters.

Frequently, the sentence was that compensation was paid by the guilty party to the injured party. The law provided for standard amounts of compensation, depending on the injury and the status of the parties involved. But the most common sentence was outlawry. The guilty party was placed outside the bounds of society. Someone subject to full outlawry (skóggangur) was banished from society. His property was confiscated. He could not be fed or sheltered. Wherever he went, he could be killed without penalty by anyone who saw him. Lesser outlawry (fjörbaugsgarður) differed in that the guilty party was banished for only three years. His property was not confiscated, making it possible for him to return to a normal life after the three years was over.

The magnitude of the punishment of full outlawry should not be underestimated. Not only was there the psychological terror of loneliness due to exclusion from all social contacts, there was also the very real threat of violence and death from unrelated third parties who sought to increase their own prestige by killing an outlaw.

|

The outlaw sagas (such as Gķsla saga and Grettis saga) emphasize the relentless alertness required of an outlaw in order for him to stay alive for any length of time. Gķsli moved his family to the remote Geiržjófsfjöršur valley (right) after he was sentenced to full outlawry. When anyone was seen approaching, Gķsli left the house and hid in one of his hideouts (left) scattered around the valley. |

|

|

The sagas also describe the loneliness and suffering that was part and parcel of life as an outlaw. In chapter 61 of Grettis saga, it says that Grettir lived for a winter in Žórisdalur behind Prestahnjśkur (left), with a family of giants. Having visited that forlorn spot, I can say that only a giant or an outlaw would choose to live in such a desolate and forbidding place. (However, the saga further says that Grettir had some fun with the giant's daughters, so perhaps the place was less forlorn than when I visited.) |

A lesser outlaw retained some degree of protection. Both Grįgįs (K52-K53) and the sagas (notably, Vķga-Glśms saga chapter 19) tell us that a lesser outlaw had three places of safety. He was immune from attack at those three places, or within a bow-shot of them, or on the roads that connected the three places, as long as he moved more than a spear-length off the road should other travelers pass by. A lesser outlaw retained that immunity for a period of three years, if, each summer, he asked for passage out of Iceland of at least three ships.

|

A lesser outlaw who failed to observe these requirements as specified by law became a full outlaw. as happened to Vigfśss Glśmsson in Vķga-Glśms saga. As a lesser outlaw, he could not stay at his father's home, since the home was the site of a temple to Freyr, and thus sanctified. Outlaws were not permitted in such holy places. He stayed there regardless, where his father secretly sheltered him, and so he was declared a full outlaw. The temple is thought to have been located at Hripkelsstašir, shown to the right as it appears today. |

|

In addition to the participants in politics and law, the Alþing attracted all sorts of merchants, craftsmen, and peddlers. The annual meeting was the time for marriages to be arranged, alliances to be made and broken, friendships to be renewed, and gossip and news exchanged. Perhaps one thousand people routinely attended the Alþing, although many more attended important or contentious sessions. Despite the sparseness of the Icelandic population, the Alþing made it possible for Icelanders to know one another to a greater degree and to meet each other more often than any other European country of this time.

|

While attending the žing, people lived in bśðir (booths), structures with a permanent stone foundation which were "tented over", topped with a temporary fabric roof while the žing was in session. Booth ruins are visible at Þingvellir (right) and many of the regional žing sites. While the žing was in session, a goši was required to provide booth space for his men. |

|

|

Construction details and the size of typical bśðir are not known. Previously, bśðir were thought to be fairly large and roomy structures. However, a recent dig at Biskupsbśš (left) at Þingvellir suggests that earlier interpretations were wrong. Rather than being one one large structure, the ruins represent ten or more different bśðir built at different times on the same site. The evidence suggests that bśðir were quite small. |

A romantic would like to believe that the booth ruins visible today are the same structures in which Skarphéšinn insulted and threatened Žorkell hįkur (Njįls saga chapter 120), or in which old Žorbjörn bent Žorgeir's injured toe (Hrafnkels saga chapter 9), or any one of dozens of memorable episodes from the sagas. However, all the ruins visible at žing sites around Iceland date from the 19th or late 18th century. To my knowledge, no ruins of commonwealth era booths are visible.

The site of the Alþing was hallowed. The allsherjargoši (the goši of all people) hallowed the site as part of the opening ceremonies. The allsherjargoši was the goši who held the gošorš originally belonging to Ingólfr Įrnarson, the first settler in Iceland. A truce was nominally observed during the žing, with weapons laid aside or secured with frišbönd (peace straps). The meeting was closed with a vįpnatak, the taking up of weapons. Ancient writings (e.g., Tacitus Germania chapter 10) suggest that weapons were clashed to signify assent during assemblies, but nothing in the later medieval documents would seem to support that suggestion.

|

Virtually any free men could choose to attend. Þingvellir is about 50 km (30 miles) inland from the modern location of Reykjavík. Some may have traveled by ship to Hvalfjöršur or Borgarfjöršur and then made the short overland journey. Most rode to Þingvellir. However, some had to make a long and arduous journey to reach Þingvellir, traveling across the interior (right) through hundreds of kilometers of desolation. For those who lived in the remote Eastern Quarter, the total time taken up by the Alþing, including travel time, might have been as long as seven weeks, a significant fraction of the short Icelandic summer. |

|

|

|

The site of the Alþing was close to most of Iceland's population centers, so for much of the population, it was convenient to reach. The site abounds with natural resources, so once people arrived at Þingvellir, many of their most essential needs were met. The plains provided space for men and their dwellings, the temporary stone wall bśðir. Today, the stone ruins of the bśš walls (left) can be seen dotting the plain. |

|

The river and adjacent lake (Žingvallavatn seen in the photo to the right) provided water for cooking and bathing, and abundant food, in the form of fish. As a result, Alžing attendees had no need to carry food with them to eat while the assembly was in session. The gorge Hestagjį (right, foreground) served as a natural corral in which horses could graze while being safely confined. Nearby woods provided the fuel for cooking fires. |

|

|

From the stories (e.g., chapter 5 of Orms žįttur Stórólfssonar), we know that there was a brewhouse on site. The remains of the farm where the ale was probably brewed are still visible (left). |

|

The rock cliff behind Lögberg served as a natural reflector to allow the words of the law speaker to be clearly heard by all. |

|

|

|

The appearance of the site has changed over the last 1000 years. Geological forces have altered the topography of the site. The floor of the plain has subsided, so that the river and lake now flood more of the plain. |

|

The Law Rock has subsided into a grassy mound. Indeed, there is some uncertainty about the actual location of these historical sites, such as Lögberg, in the saga age. |

|

|

Regardless, it's hard not to stand in awe of both the physical beauty and the historical significance of the site. |

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |