|

|

Viking Raids

|

Much of the text presented on this page is out-of-date. Until we find time to make the needed updates to this page, we strongly encourage readers to look at this topic as it is presented in our new book, Men of Terror, available now from your favorite book seller. |

|

The aspect of Norse society that most captures the modern popular imagination is the Viking raids. The historical records of Europe (written for the most part by the educated clergy who often were the victims of these raids) called the raiders "a most vile people". But the raiders themselves certainly didn't hold that opinion. To them, the raids were a normal and desirable consequence of the pressures on a growing society and of the religious beliefs of the time. It's worth noting that raids similar to those conducted by the Vikings occurred in other parts of Europe during the Viking era. What made the Viking raids so notable was their success (due in large part to the superiority of Viking ships) and their extent (well outside the borders of the Norse lands). |

In the mind of the Norse people, raiding was very distinct from theft. Theft was abhorrent. According to the Norse mythology as told in Snorra Edda, theft was one of the few acts that would condemn a man to a place of torment after his death. On the other hand, raiding was an honorable challenge to a fight, with the victor retaining all of the spoils.

A story from chapter 46 of Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar illustrates this distinction. While raiding a coastal farm, Egill and his men were captured by the farmer and his family, who bound all of the raiders. In the night that followed, Egill was able to slip his bonds. He and his men grabbed their captors' treasure and headed back to the ship. But along the way, Egill shamefully realized he was acting like a thief, saying, "This journey is terrible and hardly suitable for a warrior. We have stolen the farmers money without his knowledge. We should never allow such shame to befall us."

So, Egill returned to his captors' house, set it ablaze, and killed the occupants as they tried to escape the fire. He then returned to the ship with the treasure, this time as a hero. Because he had fought and won the battle, he could justly claim the booty.

Raiding was a desirable occupation for a young man, although a more mature man was expected to settle down and raise a family. This view of raiding is described by Ketill to his son, Žorsteinn, in chapter 2 of Vatnsdęla saga. Ketill was not pleased that his son had taken no initiative in rooting out a highwayman working nearby who had killed dozens of travelers. Ketill said to his son, "The behavior of young men today is not what it was when I was young." He said that it was once the custom of powerful men to go off raiding, in order to win riches and renown for themselves. Even if sons inherited their family lands, they were unable to sustain their high status unless they put themselves and their men at risk and went into battle, winning wealth and renown for themselves. Ketill concluded by saying to his son, "You have now reached the age when it would be right for you to put yourself to the test and find out what fate has in store for you."

Raiding increased a man's stature in Viking society. A successful raider returned home with wealth and fame, the two most important qualities needed to climb the social ladder.

Raiding was often a part-time occupation. Chapter 105 of Orkneyinga saga describes the habits of Sveinn Įsleifarson. In the spring, he oversaw the planting of grain on his farm at Gįreksey. When the job was done, he went off raiding in the Hebrides and Ireland, but he was back to the farm in time to take in the hay and the grain in mid-summer. Then he went off raiding again until the arrival of winter.

A Viking raid on a farmhouse is Norway is described in the chapter 1 of Hallfrešar saga. Sokki, a vicious Viking, came to the house of Žorvaldur, a wealthy farmer. In the night, the Vikings set the house ablaze. Žorvaldur came to the door and called out, asking who was responsible and why he deserved such ill treatment. Sokki replied, "We Vikings are after your life and your goods," and they attacked with fire and with weapons. Some of the household escaped, but most perished. The Vikings took away all the loot they could carry.

| The loot that Vikings desired was anything of value that was compact

enough to carry on-board their ships. That included gold and silver, but

also included iron tools and weapons, as well as clothing and food, all valuable

items. Captured livestock was often slaughtered on the spot to provide

fresh food for the raiders.

Another form of valuable taken in raids were people, to be sold as slaves. The sagas provide few details of this kind of booty, but in chapter 13 of Laxdęla saga, Melkorka Mżrkjartansdóttir says she was taken as war booty when she was fifteen years old. |

|

One has the sense that Viking raiders also conducted legitimate trade while on their voyages. Chapter 46 of Egils saga says that while Egill and Žórólfur were raiding in Kśrland on the Baltic one summer, they halted their raids, called a two-week truce, and began trading with their former victims. Once the truce was up, the Vikings returned to attacking and plundering, raiding the places that seemed most attractive.

One has to wonder if during the truce, the hapless Kśrlanders bought back some of the things taken from them in the raids, and afterwards if the Vikings targeted certain farms to take back through force some of the more desirable goods that had been purchased from them.

The raids escaped the notice of the rest of Europe until the raiders started attacking targets outside of Scandinavia. It's not clear what triggered this outward movement at the end of the 8th century. Perhaps it was due to population pressure, since portions of Scandinavia were overpopulated by the standards of the time. Alternatively, changes in trading patterns in northwest Europe in the century before the Viking age may have been the trigger that started the outward movement from the Norse lands. The new trade routes and trade centers exposed the Norse people to the magnitude of the wealth changing hands, and to the conflicts and politics of European kingdoms, revealing both the benefits of and the opportunities for raiding outside the Norse lands.

|

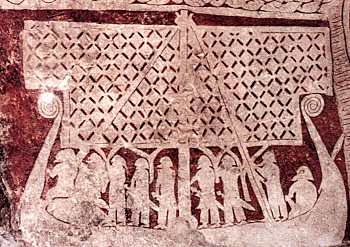

Regardless of the trigger, the Norse people started moving outwards from Scandinavia at the end of the 8th century, interacting with and making their mark upon other Europeans. The start of this movement defines the beginning of the Viking age. The first recorded Viking raid occurred in the year 793, against the great monastery of Lindisfarne off the northeast coast of England. The grave marker from Lindisfarne shown to the left records that attack. |

|

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (a contemporary history of the Anglo-Saxon people) for that year reads:

|

|

The attack sent shock waves throughout Europe: why had God allowed such a holy place to be defiled by pagans?

Monasteries were frequent targets of Norse raiders not because the raiders were particularly anti-Christian, but rather because that's where the money was. The tithes collected by the church concentrated the wealth in the monasteries during this period. The raiders recognized that fact and took advantage of it.

|

As they expanded, the Norse were looking for three things: new victims to raid; new partners with which to trade; and new land on which to settle. In many cases, Norse voyages included all three activities. The raids were usually opportunistic, against targets that could be attacked, plundered, and departed from quickly. Vikings stayed along the coast or on navigable rivers; overland marches were avoided. The goal was to grab as much valuable booty as possible before an effective defense could be raised. Typical booty included weapons, tools, clothing, jewelry, precious metals, and people who could be sold as slaves. The size of the raiding parties varied. A small raiding party is described in chapter 46 of Egils saga. Egill and Žórólfur led separate groups of twelve men each from their shared longship. A larger party is described in chapter 29 of Njįls saga. Gunnar and Hallvaršur began their raiding party with two ships, one with forty oars, and one with sixty. At the end of the summer, they returned from their raids with ten ships. One of the largest raiding parties was the Great Army which harried in England and the Continent and which probably numbered in the few thousands. Raiding parties were tightly knit groups, working together, with the spoils shared out amongst the group. Chapter 43 of Vatnsdęla saga tells of a raiding party which included Žorkell. He was outraged to have been left behind during a raid, especially because he was delayed by fighting alone against six opponents to acquire a valuable treasure. He chastised the earl who led the party: "I have heard you say that men should run from ship to shore, but never that one should run back to the ships in such a way that each man abandons the next." The earl agreed and ordered than any man running away would have no share of the spoils. |

The Viking raiders depended on the superiority of their ships in order to make their raids a success. The shallow draft of Viking age ships meant that they could navigate shallow bays and rivers where other contemporary ships couldn't sail. The broad bottom of the Viking ships made it possible to land on any sandy beach, rather than requiring a harbor or pier or other prepared landing spot. These two factors made it possible for Vikings to land and raid in places that their victims thought it impossible to land, contributing to the surprise of the raids. Additionally, the efficiency of Viking ships under sail meant they could outrun contemporary ships under favorable conditions. And the combination of sail and oar meant that Viking ships could outrun contemporary ships under unfavorable conditions as well. These two factors made it possible for Viking raiders to depart from a raid with little danger from any defenders who might try to give chase.

The cruel and bloody portrayal of these raids has probably been overstated. The exaggerations have occurred in the writings of authors from several eras: by the contemporary authors who originally described the raids (learned Christians who were inimical to the pagan Norse and who may have been the victims of the raids); by the later Nordic authors who had pride in the exploits of their forebears (such as the authors of the Icelandic family sagas); by later historians from other European lands who wanted to highlight the courage shown by their forebears against the Viking onslaught; by later Nordic historians who had developing feelings of nationalism (such as the authors of some of the first Scandinavian histories); and by modern authors who may have misinterpreted earlier texts. For example, the sadistic ritual killing known as a "blood-eagle" in some of the descriptions of Viking raids is almost certainly a literary invention from later times. |

|

One has the sense that while the motives of raiders shared some similarities (wealth, fame, and occasionally revenge), the details of how they operated differed in significant ways. The sagas talk about "Robin Hood"- like raiders, such as Žorgils and Gyršur, described in chapter 16 of Flóamanna saga. They attacked gangs of thieves and robbers and plunderers, but let farmers and traders go in peace.

Svarfdęla saga (ch.3) tells of Žórólfur and his brother, Žorsteinn, who was a successful trader. The brothers decided to go raiding together because they wanted to enhance their bravery, rather than their prestige. Žorsteinn sold his knörr (trading ship) and bought two longships. After three years of raiding, the brothers owned twelve ships and great wealth.

At the other extreme, Surtur jįrnhaus (Iron-Skull) was a great viking and evil-doer who raided all over the British Isles, abducting women and fighting duels, as is told in chapter 15 of Flóamanna saga. When Surtur challenged Earl Ólafur to a duel over the earl's sister, Žorgils took the earl's place in the duel and killed Surtur.

The Norse pagan religion helped to propel the Norse expansion through two key beliefs. The first is the belief that for most people, there is no existence after death. Death is the end for all but a few. These few include the chosen warriors who enjoyed the pleasures of Valhöll after death. And they include oath breakers, thieves, and the like who, after death, were taken to Niflheim for torment. Since there was no afterlife, the only thing that survived after death was one's reputation, one's "good name". Norsemen risked everything to gain and protect their good name.

The second key belief of Norsemen is that the time of one's death is determined by fate and is chosen by the Norns at the time of one's birth. Therefore, nothing one did could change the moment of one's death. However, what one did up until that moment was strictly one's own doing. Therefore, one ought to make the very best of every moment of life, because the worst that could happen would be death, and the best that could happen would be fame and an enhancement to one's reputation. Since one couldn't effect the time of one's own death, which was predestined anyway, there was nothing to lose and everything to gain by being bold and adventurous.

This attitude towards life is expressed in an address made by King Sverrir of Norway to his troops before the Battle of Ilevolden (described in chapter 47 of Sverris saga). The king related a parable to his men:

|

|

A good man (drengr) was expected to face challenges with courage and equanimity. Worrying or complaining did nothing to improve the situation and only diminished a man. The greatest test of a man was to fight to the bitter end, even in the face of certain defeat and death. Norsemen expected a share of trouble, and the best of them attempted to use it, and to rise above it creating fame for themselves through bravery, loyalty, and generosity.

As

a result of these two key tenets of the Norse pagan religion, it

is only natural that raiding became a common way to increase one's

stature in the community.

Historians call this era the Viking era. Throughout these pages,

I've tried to avoid that term because while most Vikings were Norse,

very few Norsemen were Vikings. In the old Norse language, the

word vķkingr would normally be translated as raider

or pirate. While this aspect of Norse life was very important, most

Norsemen were not pirates, but rather farmers, traders, smiths, and so on.

The Viking raids didn't come to an end with any singular event. Some would say the widespread conversion to Christianity in the Norse lands at the beginning of the 11th century signaled the end of the Viking age. The teachings of the Christian religion did not encompass the kinds of activities that took place on a typical raid.

In the year 1066, King Haraldr haršrįši of Norway died trying to conquer

England. It would be the last major Norse raid. In the same year, Polish

tribesmen overran and destroyed Hedeby, the primary Norse trading center. The

climate turned colder that century, making life more difficult in the north. The

Norse influence in continental Europe gradually declined.

|

|

©1999-2025 William R. Short |