|

|

Viking Age Arms and Armor

Available Sources

|

Much of the text presented on this page is out-of-date. Until we find time to make the needed updates to this page, we strongly encourage readers to look at this topic as it is presented in our new book, Men of Terror, available now from your favorite book seller. |

|

Our knowledge of Viking arms and their use comes from a small number of sources. Alone, none of these sources paint a clear picture how Viking-age warriors used their weapons. Taken together, our understanding, although speculative, becomes more clear. |

|

Perhaps our most important source of information are the Sagas of Icelanders. The sagas are stories set in Iceland and the other northern lands in the Viking age. They were written down in Iceland after the close of the Viking age. The sagas are unique among medieval European literature. They were written in the vernacular, old Icelandic, rather than in Latin. They were a new literary form created in Iceland. They tell stories not about kings and gods and trolls, but rather about ordinary men and women facing extraordinary challenges as they lived their lives in the Viking age. Today, they remain fascinating, entertaining reading, telling compelling tales about interesting and lively characters. |

|

The accuracy of the sagas is highly contentious. They are not histories, but they are based on actual events and historical characters. It is likely the details were manipulated by the author to meet his literary needs. Regardless, we believe there is a large body of genuine historical information in the sagas.

|

Fights are often mentioned in the sagas. Our research now leads us to believe that the saga authors were experienced fighters, writing for an audience made up of experienced fighters who would be unwilling to accept (and possibly insulted by) exaggeration in the depiction of battle. Additionally, the sagas authors seem to have been aware that weapons had changed between their own time (when the sagas were written) and the Viking age (when the sagas took place). The photo shows a fighter using weapons from the time the sagas were written (left) facing a fighter armed with Viking-age weapons. When the saga authors wrote about weapons and their use, they seem to describe weapons and moves from the Viking age, rather than from their own time. |

We believe there are many errors in the Sagas of Icelanders, such as anachronisms. We believe there are fantasy elements in the sagas. So, the sagas must be used with great care as a historical source. Yet, we are much more willing now to accept that the fighting moves described in the Sagas of Icelanders represent realistic, Viking-age fighting moves.

|

In addition to teaching us about the moves, the sagas tell us much more. The give us insight in to the mindset of the Viking-age warrior. Viking-age society was not a military society, but it is clear that fighting men carried in their hearts an unwritten set of beliefs that guided their behavior in battle. These beliefs teach us to what lengths a man would go to in order to succeed in his fight, but they also teach us the line that an honorable man would not cross. Understanding this mindset is a valuable tool in understanding how Vikings fought and how they used their weapons. |

|

These, and other kinds of information gleaned from the sagas make the sagas perhaps our best source of information about Viking-age fighting.

Bio-archaeology

Another source we use in our research at Hurstwic is bio-archaeology. We study the bones of people from the Viking age with battle injuries. These studies tell us about the types of attacks, the weapons used, the wear and damage to weapons during battle, the targets, and the power of the attacks.

|

For example, the top of this Viking-age man's skull was taken off with a single percussive cut with a sword, a cut of incredible power. How do you deliver that much power with a single-handed weapon? |

Importantly, bio-archaeology can confirm some of the things we read in the sagas. The sagas sometimes tell of fights and injuries that are incredible: so over-the-top that we simply can not accept them as anything other than heroic excess on the part of the saga authors.

|

But the bones provide mute testimony that, at least in some cases, these kinds of horrific attacks, and horrific injuries actually took place. The sagas tell of men receiving multiple wounds, any one of which would be lethal, yet continuing to stand and fight. This skull (part of a complete skeleton) tells us that at least in some cases, these events actually happened. The skeleton bears evidence that the man had 2 lethal wounds and several less serious wounds yet was still standing and fighting when a sword penetrated his skull, entered the brain, and killed him. |

|

The sagas tell of men receiving horrific wounds but surviving, recovering, and living to fight again another day. The bones tell us that sometimes, it actually happened. We find skeletal remains in which the same individual had serious injuries that have healed and serious injuries that did not heal. He was injured in a battle, healed, and lived to fight another battle in which he died, as is sometimes described in the sagas. And so, the bio-archaeological evidence add weight to the evidence from the sagas.

|

At Hurstwic, we are also doing experimental bio-archaeology. We make test cuts with sharp replica weapons to animal carcasses, usually pigs. We try some of the moves we believe were used by Viking-age warriors, including moves described in the sagas. Then we look at the effect of these moves on flesh and bone. Do the weapons cut as described in the sagas? Often, the answer is yes. When the sagas say (as they often do) that the axe split the skull down to the shoulders such that the teeth fell out, we know that is no exaggeration. But sometimes, the answer is no, the weapons do not cut as described in the sagas, which leads to more research and experiments about how Viking-age weapons were used. |

|

After a cut, we look at the bones to see if they show the same kind of damage we see in Viking-age human skeletal remains. We make cuts to replica Viking-age armor to see if it provides the kind of protection we would expect from the descriptions in the sagas. A video summary of some of our cutting tests can be seen in this YouTube video. |

|

Some very recent unpublished studies throw some doubt on the use of skeletal-remain evidence. Skeletal remains excavated in Dalvík in north Iceland suggest some bizarre burial practices, in which the skeletal remains were dug up and reburied multiple times in a relatively short period of time (2 or 3 generations). The marks thought to be made by shovels on the bones appear very similar to marks made by weapons. While some of the trauma seen is unmistakably due to weapons, some might have a more prosaic explanation.

|

Another valuable source of information is archaeology: what we dig up out of the ground. During the Viking age, most people practiced the old northern pagan religion and, worshipping the gods and goddesses of the Norse myths. |

|

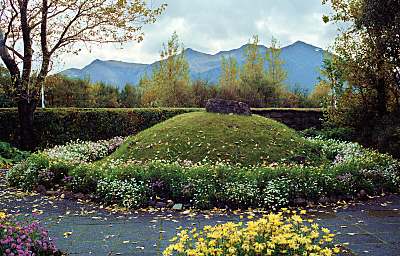

Their burial practices included being buried with grave goods: a few of the things they used in their everyday lives. Egils saga tells us that Egill had his father Skallagrímur buried with his weapons, his horse, and his blacksmith tools. |

|

|

These graves still exist today. Skallagrímur's grave is shown as it appears today to the left. We can excavate these grave sites and study the contents. |

|

But few weapons survive. In the ground, the wood and leather rot, and the iron rusts away. So it is only under unusual conditions that any Viking-age arms and armor have survived. Only one more-or-less complete Viking-age helmet has been found, in Gjermundbu, Norway (right), and even that example has many pieces missing (which are grayed-out in the photo). |

|

|

Often, the weapons are found in poor condition: rusted, pitted, and highly eroded, with their blades turned into iron lacework that disintegrates with a touch. |

|

Yet under unusual conditions, some weapons have survived from the Viking age in excellent condition. The Viking-age sword shown to the left (with a modern replacement grip) is still bright and shiny. The Viking-age sword shown to the right is robust enough to swing and use to try some moves. |

|

Despite the limited number of finds, and the imperfect condition of the recovered artifacts, archaeology is our best source of information about Viking-age weapons.

An additional source of information comes from art. While the Viking people prized art, and left behind many beautifully decorated objects, they left few realistic representations of the human figure.

|

What survives is a small number of stone carvings, wood carvings, bone and horn carvings, and tapestries. Often, they are representations of stories from mythology and from heroic tales. Grave markers (right) and memorial stones (left) sometimes show warriors dressed for battle. |

|

|

Some figurative art from other European societies during the Viking age has survived, such as the sketch of mounted Carolingian warriors (shown to the left). The illustration was drawn in the 9th century and depicts a contemporary scene. |

Since so few pictures of warriros and their weapons survive, the pictorial sources have limited value in our research of Viking combat.

|

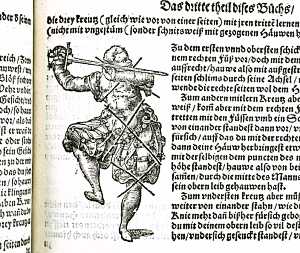

Well after the end of the Viking age, skilled fighters wrote training manuals to help teach students how to fight. These later combat treatises include manuscripts such as the Royal Armouries Manuscript I.33 (left), and books by Talhoffer, Mair, and Meyer (right). |

Image ©2006 Higgins Armory Museum |

At one time, we felt that these medieval and Renaissance manuals could help us in our understanding of Viking-age fighting. We no longer hold that belief.

|

It is very clear that the weapons from the time when the manuals were written differ in significant ways from the weapons of the Viking age. The photo shows a man using Viking sword and shield facing a man using Meyer's longsword. Since the weapons differ in such significant ways, it would not be a surprise that the fighting moves would also different in significant ways. |

|

But more importantly, it is more and more clear from our studies of the sagas that the mindset of the Viking age warrior differed greatly from the mindset of the medieval and Renaissance fighter trained using these combat treatises. This significant difference in mindset means that these fighters, from different eras and different cultures, used their weapons differently than Viking-age warriors.

Thus, we no longer find the material in the later combat treatises to be a useful source in our study of Viking-age fighting.

[Our research evolves and grows but regrettably, these web articles sometimes don't reflect our current thinking on some topics. As a result, many of our old ideas about the treatises as a source remain in some of the articles on this site. We regret the confusion this may cause, and we hope to update these articles when time permits.]

Summary

None of the available sources tell the full story of how Viking-age people fought. But taken together, the sources make the story more and more clear. Regardless, the moves, tactics, and techniques described in these web articles represent the author's opinion about Viking-age fighting based on the limited historical material available.

|

|

<< Previous article |

Back to Arms and Armor |

Next article >> |

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |