|

|

Viking Age Arms and Armor

Viking Swords

|

Much of the text presented on this page is out-of-date. Until we find time to make the needed updates to this page, we strongly encourage readers to look at this topic as it is presented in our new book, Men of Terror, available now from your favorite book seller. |

More than anything else, the sword was the mark of a warrior in the Viking age. They were difficult to make, and therefore rare and expensive. The author of FˇstbrŠra saga wrote in chapter 3 that in saga-age Iceland, very few men were armed with swords. Of the 100+ weapons found in Viking age pagan burials in Iceland, only 16 are swords.

A sword might be the most expensive item that a man owned. The one sword whose value is given in the sagas (given by King Hßkon to H÷skuldur in chapter 13 of LaxdŠla saga) was said to be worth a half mark of gold. In saga-age Iceland, that represented the value of sixteen milk-cows, a very substantial sum.

Swords were heirlooms. They were given names and passed from father to son for generations. The loss of a sword was a catastrophe. LaxdŠla saga (chapter 30) tells how Geirmundr planned to abandon his wife ŮurÝr and their baby daughter in Iceland. ŮurÝr boarded Geirmund's ship at night while he slept. She took his sword, FˇtbÝtr (Leg Biter) and left behind their daughter. ŮurÝr rowed away in her boat, but not before the baby's cries woke Geirmundr. He called across the water to ŮurÝr, begging her to return with the sword.

He told her, "Take your daughter and whatever wealth you want."

She asked, "Do you mind the loss of your sword so much?"

"I'd have to lose a great deal of money before I minded as much the loss of that sword."

"Then you shall never have it, since you have treated me dishonorably."

Swords in the Viking age were typically double edged; both edges of the blade were sharp. Swords were generally used single handed, since the other hand was busy holding the shield. Blades ranged from 60 to 90cm (24-36 in) long, although 70-80cm was typical. Late in the Viking era, blades became as long as 100cm (40in). The blade was typically 4-6cm wide (1.5-2.3in). The hilt and pommel provided the needed weight to balance the blade, with the total weight of the sword ranging from 2-4 lbs (1-2 kg). Typical swords weigh in at the lower end of this range. Blades had a slight taper, which helped bring the center of balance closer to the grip.

|

The modern reproduction shown in the photo above and to the left was made by Jeff Pringle and is a copy of a sword from the late 10th century found in the River Thames in London. Like the original, the reproduction blade has a greater taper than is typical for Viking age blades. The blade of the reproduction is 66cm (26in) long. Both the original and copy have an intricately fabricated iron inlay on the blade, and precious metal inlay on the hilt and pommel. The copper and silver herringbone inlay design used on the reproduction was taken from an early 10th century Norwegian sword. |

|

The photo shows a well-preserved Viking-age sword that dates from around the year 950. It's an exquisite example of the bladesmith's art from the Viking age. The overall length is 89cm (35in), and the blade length is 77cm (30 in). The total weight is 1.04 kg (2.3 lbs). The sword was well used during its lifetime, showing battle scars and evidence of honing along the length of the cutting edges. The balance of the weapon in the hand is extraordinary, and it becomes an extension of the swordsman's arm, eager to go where directed. The sword bears the ULFBERHT mark as an inlay in the blade, discussed later in this article. |

|

|

The tip of the blade came to a point, which, rather than being acute, was usually somewhat rounded, as is seen on the seven historical Viking-age sword blades shown to the left. The rounded point is stronger than an acute point, but no less effective for stabbing and thrusting. |

|

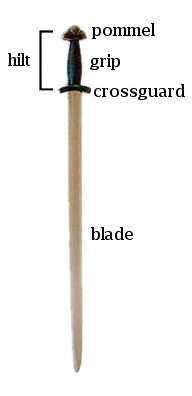

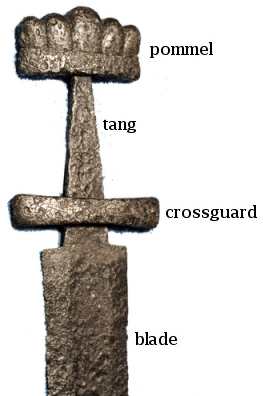

The parts of a sword are called out in the photo of the modern reproduction sword shown to the left. The hilt is made up of the pommel, grip, and crossguard, and is shown in more detail on a historic sword to the right. The organic materials making up the grip have decayed and fallen away in the thousand years since this blade was made, revealing the tang, the narrow extension to the blade that passes through the crossguard and grip and fastens to the pommel. For this photo, the crossguard was pulled up from the blade to reveal the shoulder, where the blade narrows to form the tang. |

|

|

Both edges of the physical blade are nominally identical. However, in describing sword technique, it is useful to distinguish one edge from the other, since they are used in different ways. Double edged swords have what is known as a front edge and a back edge (right). The front edge is the "front" of the blade, the edge in line with the knuckles, and it is sometimes referred to as long edge or true edge in later combat treatises. The back edge is the "back" of the blade, and it is sometimes called short edge or false edge. The two edges are physically identical; which edge of the blade is long and which is short depends only on which way in the hand the sword is being held. But, the two edges are used differently. The front edge is used for powerful attacks, while the back edge permits angled attacks with greater reach. |

|

The crossguard of the middle hilt has

been pulled up |

The photo above shows two historical Viking swords. The top sword is 103 cm long overall (40.5 in) and weighs 1.59 kg (3.5 lbs). The bottom sword is 89 cm long overall and weighs 1.04 kg (2.3 lbs). A U.S. quarter between the blades helps show the scale. Both blades appear to have an ULFBERHT inlay (described later in this article), suggesting that they're both fine blades. (The inlay has been brought out and is clearly visible in the bottom sword, and is vague in the top sword, but more clear in X-ray images.) The sketches to the right show some of the variations in size and shape that existed in Viking-era blades and hilts. The photo to the left shows five Viking era sword hilts, illustrating the variations in guards and pommels that existed during the Viking age. The hilts are generally classified using a system devised by Jan Petersen and published in 1919. Since a given style was in use only during a given period, the hilt style can be used to help date a sword.

|

|

|

For example, the Petersen Type B hilt shown to the left indicates that the sword was probably made between the middle of the 8th century and the early part of the 9th century. Not only did the size and shape of the hilt components vary in Viking-age swords, but also the construction details. Sword hilts typically had a pommel and an upper guard, although in some instances, the two were formed as a single piece. |

|

In some cases, the pommel attached to the tang, and the upper guard fastened to the pommel, as seen in the left-most sword in the photo to the left. The peened tang end is clearly visible in the photo. In the photo to the right, the upper cross of the sword has been pulled away, showing more of the construction details. In other cases, the upper guard was attached to the tang, and the pommel fastened to the upper guard, as seen on the right-most sword in the photo to the left. In the centuries that this sword lay in the ground, the pommel separated from the upper guard and was lost. These sorts of variations can be used to help date a sword. |

|

|

Hilt components were decorated using several techniques, including scribing and wire inlays. Some historical sword hilts are shown to the left, and a modern reproduction is shown to the right, inlaid with silver and copper. |

|

|

The inlay was created by cutting myriad tiny channels into the iron of the pommel, and then by fitting and hammering myriad tiny pieces of wire into the channels. The work is extremely tedious and time-consuming, but it results in a striking appearance, which can also be seen in the historical sword upon which this work was based. The process is described in more detail in the article on Viking-age hilt inlays. |

|

Stories say that sometimes fighters used their swords two-handed. But the grips of surviving Viking age swords are not long enough to be held in two hands. The grip of a modern replica sword is shown to the left, and of a historical 10th century Viking sword to the right. The grips have plenty of space for one hand, even for a beefy Viking fist, but not for two. It's not clear how a sword with a grip this short could be effectively wielded with two hands. |

|

|

|

One possibility is to use the second hand to cup the wrist of the weapon hand. It seems that this kind of grip would allow substantially more power to be delivered using a one-handed weapon like a Viking sword, while allowing the second hand to be released quickly to do more work as soon as the blade passes the target. |

|

A speculative reconstruction of this two-handed grip is shown in this combat demo video, part of a longer fight. The photo and video illustrate our best guess for using a two-handed grip, but other approaches are also workable. Regardless of the details, using a second hand to pull the sword through the cut results in substantially more powerful attacks. |

|

|

The grips were made with a variety of materials, ranging from simple wooden grips wrapped with leather, to elaborately decorated grips wound with wire made from precious metals, or covered with embossed plates of precious metals. The historical sword shown to the left has a modern grip which uses a wrap made from highly speculative modern materials. LaxdŠla saga (ch.29) says that the grip of Geirmundr's sword was made from walrus ivory. Bone or ivory would have afforded a good grip even when wet from sweat or blood. Since grips generally were made from organic materials, few historical sword retain any of their original grip; the organic materials have long since rotted away (right). |

|

In the early part of the Viking age, smiths were unable to make material suitable for a sword, in the needed quantities and with the right combination of properties. Smiths made blades from many lumps of stuff: different types of iron with different properties, taken from different smelts. He selected the material that he needed, then shaped it, twisted it, and welded it to form a composite material suitable for a sword blade. The process is called pattern welding.

|

In the past, it was believed that at least part of the difficulty was that the iron making process was not understood or well-controlled during the Viking age. However, as this text is being written, experimental archaeologists are reporting that they obtain consistent, repeatable results with their experimental smelting operations using period techniques and tools (right). Perhaps Viking age smiths had much greater control over their smelting process than was previously thought. |

|

|

The smith started with a stack of iron bars with varying properties. He used soft, low-carbon iron for flexibility and hard, high-carbon iron for strength and ability to hold an edge. The photos show some of steps of pattern welding in a modern forge, in which modern tools and furnaces were used. The stack with seven layers of iron is shown to the right before being put in the furnace. On the left, the heated stack was about to be hammered together to weld it. |

|

|

The hot, welded stack is shown to the right. After it cooled, it was cut to examine the cross section (left). All seven layers of iron are visible. There are no visible voids or defects in the internal welds of the layers. |

|

|

The piece was repeatedly worked to draw out the layered bar into a longer, thinner bar (left). Subsequently, the bar was twisted, then shaped to a square cross-section. Multiple twisted bars were welded together and shaped into the finished blade (right). |

|

|

The partially worked billet on the left was used to make the pattern welded knife blade shown on the right. |

|

|

The welding and twisting process created a composite, made up of different kinds of iron that together, had the necessary strength and flexibility for a sword blade. A detail of a modern replica pattern-welded sword blade is shown to the left. |

|

The pattern welding process was independently invented by many other cultures in the world. The photo to the right shows a detail from an Asian pattern welded blade. |

|

Despite using this pattern welding process, sword blades from the Viking age were far from ideal. In most cases, the edges were fabricated with hard steel strips in order to provide a material better able to hold a sharp edge. Even so, some stories describe how, during an extended battle, swords became so dull that they no longer cut. In chapter 109 Ëlßfs saga Tryggvasonar, at the Battle of Sv÷lr, King Ëlßfr asked his men why they cut so slackly (slŠliga), since he could see the blades did not bite. His men replied that their blades had become too dull and dented to cut.

|

Forensic evidence suggests that blade edges received substantial damage during a fight. When a worn or damaged blade severs a bone, nicks and burrs in the edge of the blade create parallel striations in the severed ends of the bones. These striations remain visible in the skeletal remains today (left), providing clues about the condition of the sword blade that made the cut back in the Viking era. Even modern replica blades (right) made from modern steel suffer edge damage in heavy fighting. |

|

|

|

It can be hard to assess the damage to Viking age blades from the archaeological records. In their excavated state, many blades show substantial erosion, especially along the thin edges and points. |

|

During the blade's working life, edge damage had to have been repaired, or else the blade was at risk of catastrophic failure. A nick was a site from which damage could propagate across the blade resulting in the kind of failure seen in this historical blade (right). Clear signs of brittle fracture are visible. It could not have been a good situation for the fighter holding the sword when it happened. |

|

|

|

If nicks and other edge damage were repaired by grinding away a portion of the blade, we might see historical blades whose edges are no longer straight, and indeed, the archaeological record contains blades with these features. An sketch showing this feature in exaggerated form is shown to the left. |

The sagas confirm that swords could be damaged or broken by striking metallic or other hard objects. In chapter 13 of Gull-١ris saga, Ůorbj÷rn's sword blade broke when he hit ١rir's helmet with it. Hrafn hit Gunnlaug's shield with his sword so hard that the sword broke off below the hilt, as told in chapter 11 of Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu. EirÝkr delivered a powerful cut at Ůorljˇtr, breaking his sword blade in two as is told in chapter 30 of HeiarvÝga saga. EirÝkr picked up the broken end of the blade and struck again, killing Ůorljˇtr.

VatnsdŠla saga (ch. 39) says that ١rir went out to catch a horse with the bridle tied around himself. Along the way, he made an assassination attempt on Gubrandur. The attempt failed, and Gubrandur struck back at ١rir with his sword. The sword hit the bridle ring, and took a finger-sized notch out of the blade. The saga author adds that the sword was resharpened and was the best of weapons.

|

Archaeological evidence shows that weapons were sometimes repaired after they suffered catastrophic failure. Several surviving swords have blades that were broken in two and then welded back together and returned to use. |

|

|

The stories also give examples of broken weapons that were repurposed and forged into other weapons. In chapter 11 of GÝsla saga, ŮorgrÝmr and Ůorkell took the broken pieces of the sword Grßsia and made them into a spearhead that measured one handspan in length. ŮorgrÝm's forge was located in the Haukadalur valley, shown to the left as it appears today. Later, the spear was used to kill first VÚsteinn VÚsteinsson and then later, ŮorgrÝmr Ůorsteinsson. The spear turned up again, over 200 years later. Sturla ١rarson wrote in ═slendinga saga (chapter 39) that the same spear Grßsia was used to kill Bj÷rn Ůorvaldsson at Breiabˇlstaur. |

|

The broken sword shown to the right was repurposed into a beater, used to force the weft threads tightly together when weaving fabric. The broken pattern welded blade was fitted with a wooden hilt, having a wooden crossguard and pommel. |

|

|

The stories also describe instances in which a sword blade bent during a fight. In chapter 49 of LaxdŠla saga, Kjartan was ambushed as he rode up the valley past the small hill in the foreground of the photo. He was not carrying his usual sword, a gift from the king, but rather a lesser sword. Several times during the battle, Kjartan had to straighten his bent blade by standing on it. |

|

In addition to creating a more suitable blade for fighting, the pattern welding process creates a work of art; beautiful, delicate patterns are created in the surface of the blade as the different types of iron came to the surface. The pattern in the surface of a reproduction blade is shown to the right. |

|

|

Bladesmiths often combined several twisted bundles together in artistic arrangements. For example, bundles twisted in one direction were placed next to bundles twisted in the opposite direction, creating more elaborate patterns. One sometimes wonders how much of the twisting was done for decorative purposes and how much to control the material's properties. The photo to the left shows a modern reproduction of a pattern welded Viking age sax (short sword). A detail of the blade is shown to the right. The difference in the patterns on two adjacent bundles is very obvious, and reflects the differing requirements of the strong backbone of the blade compared to the more flexible cutting edge. This fine pattern welding, in both the original and in the reproduction blade, shows an extremely high level of craftsmanship and control over the pattern welding process. |

|

|

As the Viking age progressed, swords changed. To some degree, this change was driven by the smith's ability to make larger quantities of better material that suited the requirements for making a blade. Instead of making the blade from several lumps of stuff, it became possible to make blades with a single lump of stuff, a process sometimes called monosteel fabrication. Yet, even though pattern welding was no longer needed, the process continued to be used for sword blades until near the end of the Viking age. Some Viking warriors seemed to prefer them, perhaps for their beauty, or their prestige. The reproduction blade shown to the right shows the appearance of a blade made out of monosteel, a single type of steel. The blade has been polished with stones and abrasives using techniques and materials known to have been used during the Viking age. Since very few sword blades survive from the Viking age with even a trace of their original finish, we can only speculate on the appearance of the surface of Viking sword blades when they were new. This reproduction blade represents a very good guess. |

|

|

Other decorative methods were used on the blade. Blades were sometimes inlaid with metals such as iron, silver, or gold. In some cases, the inlays were simply decorative, but in other cases, they indicated the maker's name. An 11th century blade with an inlay is shown to the left. Iron inlays were created by chiseling grooves into the blade to form the letters. Pattern welded iron was drawn into wire, cut to fit, and hammered into place in the grooves. Finally, the blade was heated to forge weld the wire into place. |

|

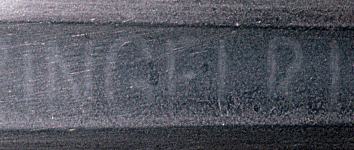

The photo to the left shows the iron inlay in a modern reproduction blade, which has been polished to the degree that would have been typical in the Viking age. The iron inlay is very subtle in normal lighting. The photo to the right shows another modern reproduction blade which has been slightly etched to bring out the appearance of the inlay. The pattern welding in the wire inlay is clearly visible. |

Sword and photo by

J. Pringle, |

|

Most blade inlays are in monosteel blades; few have been found in pattern welded blades. An example of a historical pattern welded blade having an iron inlay is shown to the right. |

|

|

All throughout the Viking period, there was changes to the length, proportions, tip, and hilt design, categorized by Jan Petersen in his book De Norske Vikingesverd published in 1919. Petersen's classifications are still widely used today. A classic example of a Petersen type K dating from the 9th century is shown to the left. Surviving Viking-age swords run the gamut from exquisite to rubbish. They vary in materials, proportions, length, balance, and weight, as well as varying in the skill of the smith who fabricated the blade. Some historical Viking-age sword jump into the swordsman's hand and become an extension of the arm, eager to do the swordsman's bidding. Other swords seem to want to resist the swordsman's will in every possible way. When one examines and wields an inferior sword of this kind, one has to ask: was this the smith's intent? Was there a warrior who wanted a weapon so unresponsive? Is there some aspect of this blade that was prized by a Viking-age fighter that we do not recognize or appreciate in modern times? Some blades have acquired a near mythic status in modern times, notably blades inlaid with the Ulfberht mark. These blades have been much discussed in popular media, often with claims that can't be supported by the evidence. |

|

Another well-known inlay marking is Ingelrii. The marks are often augmented with crosses on either end of the inlay and with inlaid geometrical patterns on the reverse side of the blade. The sketch (left) shows the Ulfberht inlay, but the artist has made the inlay much more visible than is typical to the naked eye. |

|

|

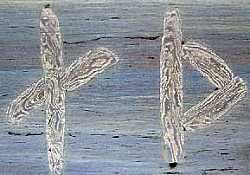

The photographs show the inlays in the reverse side (left) and front side (right) of an Ulfberht blade from the 10th century. |

|

So many swords are found, manufactured over such a wide span of years, that these swords clearly are not the work of two smiths named Ulfberht and Ingelrii. They are thought to be the products of families of sword makers, or perhaps associations of sword makers. The swords are believed to have been made in Frankish lands along the lower Rhine in what is now Germany, a region that has made fine swords and cutlery from medieval to modern times.

|

Because many of these blades are found, widely distributed throughout the Viking lands, it is believed that the Ulfberht and Ingelrii swords were prized in the Viking age and thought to be superior to other swords. It's possible that the original Ulfberht invented a new way to make a blade, using a uniform steel having a higher carbon content than the typical monosteel blades of the period. It's further possible that he chose to identify his blades with the inlay, despite the fact that the inlaid letters are extremely hard to distinguish in normal light, as is seen in the modern reproduction blade seen above and again to the left. |

|

Only when the blade is etched does the inlay stand out in sharp relief, as seen in the historical Ulfberht blade seen above and again to the right, which was etched in modern times to bring out the inlay. |

|

If we strip away the hyperbole, there seem to be three broad classes of blades

inscribed with the Ulfberht mark.

Some of the Ulfberht swords have well-made monosteel blades using good quality

high-carbon steel. Some evidence suggests that this steel is crucible steel. The process for

making this steel would have been unknown to northern smiths in the Viking age.

The steel could have come over existing trade routes from middle Eastern or Asian lands, where the process was

known. However, the evidence for the blade material being crucible steel in

Ulfberht blades is not

solid at this time. It may simply be well-made bloomery steel created using processes known to Viking

smiths.

Some of the Ulfberht swords have well-made monosteel blades using good quality

but lesser-grade steel, of the kind that could have been made by a skilled northern

smith in the Viking age.

Some of the Ulfberht swords are clearly inferior, being less-well designed and

fabricated, using lower-quality materials. In some cases, the Ulfberht mark is

poorly formed, or misspelled. At least some of these are thought to be

Viking-age counterfeits, made by smiths to capitalize on the Ulfberht name. One

surviving blade is inlaid with Ulfberht on one side and Ingelrii on the other, a

double counterfeit! The best indication of a genuine blade appears to be the

metallurgical quality, an area which has received insufficient research.

Additionally, it is likely that additional Ulfberht and Ingelrii blades remain

to be identified, since the inlays are sometimes not visible to the naked eye

and are revealed only by X-ray analysis.

It seems unlikely that nonferrous materials were used for blades in the Viking-age. Yet, in chapter 5 of FljˇtsdŠla saga, Ůorvaldur, while in a troll's cave, found a sword with a green colored blade without a spot of rust, a description suggesting the blade was made of bronze. I am not aware of any archaeological evidence for the use of bronze sword blades in the Viking age, although a bronze axe head from the Viking age survives in Iceland.

Most of the Viking age swords appear to have come from outside Viking lands, notably from Frankish lands along the Rhine. There are a few instances in the sagas in which people are described fabricating weapons, but never swords. One example is in chapter 23 of FˇstbrŠra saga, in which Bjarni made a special axe for Ůormˇur. In chapter 2 of SvarfdŠla saga, Ůorsteinn did not care for the sword he received from ١rˇlfur, so he fashioned an axe for himself.

The stories suggest that some swords were acquired as gifts: from kings; from earls; from family members. Weapons were taken from grave mounds by men brave enough to enter the grave and battle the ghostly mound-dweller.

|

It's not clear how men maintained their weapons. The stories are filled with examples where, during hard use, a weapon became so dull that it no longer cut. Sharpening weapons must have been a routine chore, as it was with agricultural implements. Men must have routinely sharpened their weapons with a whetstone. The whetstone shown to the right was found in a Viking-age context. The wear patterns indicate it was primarily used for sharpening a long-bladed weapon (such as a sword) rather than shorter weapons or agricultural tools. |

|

While generally, men sharpened their own weapons, sometimes they asked others to do the job for them. There also appear to have been professional sword sharpeners. In the battle at the Al■ing described in chapter 145 of Brennu-Njßls saga, it is said that after Skapti was wounded by a spear, he was dragged into the booth of a sword sharpener to protect him from the ongoing battle.

|

Ůorbj÷rn was a hired hand at the farm of Eyvindarß (shown as it appears today) who was skilled at sharpening and repairing weapons, as is told in chapter 9 of Droplaugarsona saga. Helgi asked Ůorbj÷rn to work on his sword while he traveled to the fjord. Ůorbj÷rn gave Helgi another sword to use while his was being serviced. That Ůorbj÷rn had a spare sword to loan suggests that his services were extensive. |

Another example of weapons maintenance occurs in chapter 18 of SvarfdŠla saga. GrÝs was outside putting oil on spearshafts, presumably to protect the wood. The word used is flot, which has the sense of fat or grease from cooked meat.

Prior to a battle, men prepared their weapons. There is a description of Njßl's sons preparing for a battle in chapter 44 of Brennu-Njßls saga. SkarphÚinn sharpened his axe, GrÝmr attached his spearhead to a shaft, Helgi riveted the hilt of his sword, and H÷skuldr fixed the handle on his shield.

Swords were highly prized heirlooms during the Viking era and were used for generations. The bas-relief shown to the right illustrates an episode from chapter 17 of Grettis saga. When a young man, Grettir prepared to leave Iceland to travel to Norway. His father had a low opinion of Grettir and refused to give him a sword, saying, "I don't know what useful thing you would do with weapons." His mother, who was more supportive, gave Grettir the sword given to her great-grandfather by King Haraldr of Norway. |

|

Some swords are mentioned in multiple sagas, spanning centuries. The sword Sk÷fnungr first appears in Hrˇlfs saga kraka (ch.52), a legendary saga set in the 6th century. The saga ends with King Hrˇlfr dying in a battle and being buried with his sword Sk÷fnungr.

Skeggi Bjarnarson, the son of an early settler in Iceland, broke into the Hrˇlf's burial mound in Denmark and took the sword Sk÷fnungr and other treasures, as is told in Landnßmabˇk (S.174). Later, Skeggi returned to Iceland with the sword, probably near the beginning of the 10th century. Kormßks saga (ch.9) says that Kormßkr tried to borrow Sk÷fnungr from Skeggi for a duel later in the 10th century.

By the beginning of the 11th century, Sk÷fnungr was in the hands of Eir, Skeggi's son as is told in LaxdŠla saga (ch.57). By this time, Eir was an old man. His kinsman, Ůorkell Eyjˇlfsson, asked to borrow Sk÷fnungr to avenge the death of Eir's son. The sword was still in Ůorkell's hands as he was transporting timber on a ship in Breiafj÷rr around the year 1026. A squall capsized the ship, and all aboard were drowned. Sk÷fnungr washed up on an island in the fjord.

Ůorkell's son Gellir came into possession of the sword, and as an old man, Gellir traveled abroad: to Norway, to Rome, and then to Denmark, where he died and was buried. Gellir had the sword with him, but the saga says its fate is unknown.

|

Archaeological evidence also supports this kind of long and continued use of sword blades. The photo to the left shows an early 11th century crossguard fitted to a blade made during the migration era, centuries before the Viking age. This evidence suggests that sword blades several centuries old continued to be maintained and used. A nearly identical crossguard was found at Hedeby, rough-worked with flashing from the casting process still visible. |

|

A sword's scabbard provided protection for the blade when not in use. Scabbards were usually made as a sandwich. The innermost lining was fleece or fabric, since the natural oils in the wool helped keep the blade from rusting. Wood surrounding the fleece provided the physical strength to protect the blade, and leather covered the entire structure. |

|

|

Scabbards, being organic, rot away, but they leave their traces on the surviving blades in ways that inform us about the scabbard construction. These close-up photos of an early 9th century Viking sword blade show the remnants of the scabbard on the blade. The photo to the left shows the full width of the blade immediately adjacent to the crossguard. The wood grain of the scabbards wooden core is clearly visible. To the right is an extreme close up of the edge of the same blade, near the point. The traces of the fibers of the fleece that formed the innermost layer of the scabbard are visible on the blade. |

|

Many scabbards had a metal chape at the tip, to protect the point of the scabbard (and sword), and some had metal mounts at the throat of the scabbard, as seen in the modern replica above.

|

The Jelling-style chape shown to the left is made of bronze and dates from the 10th century. A modern replica chape is shown to the right, mounted on the point of a scabbard. A sword without a scabbard was considered "troublesome" (vandrŠa), as in difficult to manage. In chapter 6 of Hallfrear saga, King Ëlafr gave Hallfrer a sword without a scabbard, a troublesome gift for a troublesome poet. The king said that Hallfrer must keep it for three days and three nights without harm coming to anyone. |

|

In chapter 39 of Harar saga og Hˇlmverja, Ůorbj÷rg wanted to get her husband's sword away from him so she could give it to an assassin she had secretly hired. She intentionally damaged the scabbard so that the sword fell out on its own. Rather than taking a sword without a scabbard, Ůorbj÷rg's husband took no sword when he left to settle a dispute among his friends.

There are examples in the sagas where swords stuck fast in their scabbards. In at least one case (Kormßks saga chapter 9), the sword had supernatural properties and was being abused. The sword finally came out of the scabbard howling. In another case (Hrˇlfs saga kraka chapter 23), B÷varĺs sword was stuck fast. B÷varr worried the sword back and forth fiercely until he could slide it out of its scabbard. It makes one wonder how often this sort of thing happened in actual combat. The saga also mentions that B÷var made his scabbard from birch wood.

|

Little is known about details of the scabbard, belts, baldrics, and suspension hardware, since little has survived. The organic materials rot away, leaving only the metallic chapes and belt fittings. It is thought that, early in the period, scabbards were usually slung from a baldric, a belt over the shoulder, as shown to the right. Later, swords hung directly from the waist belt. In the sagas, there are few examples of swords being slung from the shoulder. One occurs in chapter 19 of SvarfdŠla saga. SigrÝur gave Karl the sword Atlanaut. He drew the sword and slung the scabbard over his shoulder. Wasting no time, he ran outside and cut GrÝs in two with the sword. |

|

|

Some swords had a strap on the hilt which could be pulled over the hand, allowing the drawn sword to hang while another weapon was being used. In chapter 58 of Egils saga, Egill drew his sword and pulled the loop over his hand in preparation for a fight with Berg-Ínundur. During the fight, when Egil's kesja (an unknown spear-like pole weapon) stuck fast in Berg-Ínund's shield, Egil grabbed his sword and was able to run Berg-Ínundur through before his opponent could even draw his sword. A highly speculative interpretation is shown to the left. We don't know the nature of the loop (h÷nk) on the hilt of Egil's sword. Surprisingly, though, when hung from the pommel, the sword is not much in the way. After the pole weapon is dropped or shifted to the other hand, a simple flick of the wrist brings the sword up neatly into the hand. A speculative interpretation of this move is illustrated in this combat demonstration video, part of a longer fight. |

|

|

The stories talk about the use of frib÷nd (peace straps) to prevent the sword from being drawn in anger in places where its use was prohibited. An interpretation of frib÷nd is shown on the reproduction scabbard to the left. The sagas suggest that in some cases, the frib÷nd had to be untied to allow the sword to be drawn. The reproduction frib÷nd need only be slipped to the side (right) to release the sword. |

|

|

An example of the use of frib÷nd occurs in chapter 28 of GÝsla saga, at the spring assembly (vßr■ing) which took place at Ůorskafjarar■ing. Booth ruins at the site remain visible today (right). The two young sons of VÚsteinn arrived at the ■ing unrecognized. Approaching Ůorkell, they complimented him and asked to see his fine sword. Ůorkell agreed and handed over the sword in its scabbard. The boy undid the peace straps and drew the sword. Ůorkell said, "I didn't give you permission to draw the sword." The boy responded, "I didn't ask," and lopped off Ůorkel's head, avenging the death of his father by Ůorkell. |

|

In several instances in the sagas, men tried to draw their swords in haste but found them bound by the frib÷nd. In chapter 3 of Krˇka-Refs saga, Refur asked his overbearing neighbor Ůorbj÷rn for compensation. Ůorbj÷rn responded with insults and a demeaning compensation. Refur thrust out with his spear, but Ůorbj÷rn was unable to draw his hidden sword because the frib÷nd were fastened. Refur ran him through with the spear. Invariably in the sagas, this situtation ends up going badly for the unprepared fighter, but one might imagine that even a sword bound in its scabbard could be used for pommel strikes or other moves. A speculative interpretation of this move is illustrated in this combat demonstration video, part of a longer fight. |

|

Some swords had healing stones (lyfsteinn) associated with them, stones which removed the evil from an injury inflicted by the weapon. Injuries inflicted by the sword would not heal unless the healing stone was rubbed on the wound. Ůorkell borrowed the sword Sk÷fnung and its healing stone from his kinsman Eiur, as is told in chapter 57 of LaxdŠla saga. Ůorkell tracked down the outlaw GrÝmur on the heath TvÝdŠgra. In the fight, Ůorkell inflicted a wound to GrÝm's wrist, but GrÝmur wrestled him to the ground and had him at his mercy. GrÝmur chose to spare Ůorkel's life. Ůorkell rubbed the wound with the healing stone and bound the stone against GrÝm's wrist. The pain and swelling subsided immediately.

A few Viking-age swords were single-edged. These swords differ in many significant regards from the more typical double-edged Viking sword.

|

The blades typically are broad, with parallel edges nearly the entire length. One side tapers to form the point. The blades tend to be heavy and unwieldy, and the overall sense is one of crudeness. The single-edged blade shown to the left was found in the Telemark region of Norway. |

Sources suggest these single-edged swords were most common in the earliest part of the Viking age, during the transition from the Migration age. Their distribution is uneven, with finds in (for example) Dublin and in parts of Norway. Since few examples have been found in other Viking lands, it is hard to believe that these weapons were common. More likely, these were lesser quality weapons made by local smiths who lacked the tools, techniques, and materials to make higher quality double-edged blades. The thick, strong (but heavy) backbone of the single-edged blades meant that lesser materials and lesser skills could be employed, yet still result in a serviceable, if chunky, weapon.

The surviving Viking-age swords span a wide gamut. Some are magnificent works of art. Some are plain, workaday tools for combat. Some are formidable weapons that leap into the hand and become an extension to the warrior's body. Some are worthless, unbalanced lumps of iron that seem only to thwart the warrior's intention at every opportunity. It is clear that not every bladesmith was accomplished, and it is possible that some warriors struggled with inferior weapons.

|

As described in more detail in the axe article, desperate men sometimes threw their weapons at their opponents, including their swords. In chapter 39 of VatnsdŠla saga, ١rir was sent to assassinate Gubrandur, but his axe stuck fast in the door frame on the first blow. ١rir ran out of the house, across the yard and jumped a river with Gubrandur in pursuit. Gubrandur threw his sword across the river at ١rir, and by the time Gubrandur reached the other side, ١rir lay dead. |

|

Sometimes during a fight, men discarded their weapons to grapple, using empty-hand moves against their opponents. These moves included breaking the back or the neck (right), or throwing a man down to finish the fight using a secondary weapon, or even by biting out his throat if no other weapon was readily at hand. However, punches and other blows do not seem to have been used. Indeed, the wrestling move of breaking a person's back still retains its currency in modern Icelandic. "A brjˇta ß bak aftur" literally means to break the back, but the phrase is used to indicate that someone or something has been completely surpressed. |

|

|

From the stories, we know that Norsemen enjoyed wrestling and practiced it as a sport (discussed in more detail in the article on Viking-age games and sports). At the Hegraness■ing spring assembly (left, as the site appears today), young men thought it would be good to arrange wrestling matches, as told in chapter 72 of Grettis saga. Grettir was unrecognized, and he was urged to participate in the contests. Did Vikings also practice wrestling in combat? The answer clearly is yes. Again and again in the sagas, men drop their weapons and run in to grapple. The Viking age swords were short enough that, when in distance, it was only a short step to be within grappling range. When Atli was fighting ŮorgrÝmur (as is told in chapter 21 of Hßvarar saga ═sfirings), Atli saw he was making no progress in the fight. He threw away his sword and slipped under ŮorgrÝmur's guard and threw him to the ground. A speculative reconstruction of running in under a weapon to grapple is shown in this Viking combat demonstration video, as part of a longer fight. |

It seems likely that sport wrestling (right) was the way that Viking-age warriors kept in fighting trim. Many of the same moves used in sport wrestling can be used in earnest wrestling and in other forms of fighting. |

|

There are several examples in the Icelandic sagas where grappling is described as a normal part of combat. In some cases, an unarmed man grappled with an armed man who attacked him, such as in chapter 19 of Bjarnar saga HÝtdŠlakappa. As Bj÷rn walked out of the farmyard with his visitor Ůorsteinn, he realized that Ůorsteinn had come as an assassin. Bj÷rn, who was unarmed, moved away, giving Ůorsteinn an opening. Ůorsteinn raised his axe to strike, but Bj÷rn went under the axe to grapple. Bj÷rn threw Ůorsteinn down, then strangled him.

In other cases, an armed man might choose to discard weapons that had become useless, and close the distance to grapple. In chapter 65 of Egils saga, Egill and Atli's shields were so badly shattered by the exchange of blows that they became useless, and they threw them away. Egill also threw away his sword and grappled with Atli, eventually killing him by biting through his throat.

Parrying with an empty hand occasionally shows up in fights described in the sagas. In chapter 17 of Brennu-Njßls saga, Ůjˇstˇlfur attacked Hr˙tur with his axe. Hr˙tur stepped aside, and he used his left hand to deflect the axe while simultaneously attacking Ůjˇstˇlf's leg with the sword in his right hand.

Parrying with the hand didn't always work. In chapter 37 of Grettis saga, Grettir struck at Ůorbj÷rn, presumably with his sax. Ůorbj÷rn parried with his hand, but Grettir's blow struck off Ůorbj÷rn's hand and subsequently his head.

Fights could go on for such a long time that combatants might ask for a truce, or for a break in the fight to recover their strength. In chapter 9 of Gunnars saga Keldugn˙psfÝfls, Gunnar rode out to Írn's farm, knocked on the door, and told Írn to defend himself. They fought for a long time. Írn tired before Gunnar, because he was an older man, and he asked Gunnar for a pause. They rested, leaning against their weapons. When they began the fight again, Írn fought with renewed vigor, but Gunnar eventually cut through Írn's helmet and skull, killing him.

A truce during a fight was sacrosanct. It was unthinkable to break a truce, although the sagas say it occasionally happened. One such truce-breaker was Hrafn, described in chapter 12 of Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu. Gunnlaugr and Hrafn fought for a very long time. Eventually, Gunnlaugr hacked off Hrafn's leg. Hrafn dropped back onto a tree stump, while the two discussed the fight. Hrafn asked for a drink of water, and Gunnlaugr asked for and received promises that Hrafn would not trick or deceive him. Gunnalugr brought water in his helmet to Hrafn. As Gunnlaugr handed over the helmet, Hrafn struck a powerful blow at Gunnlaug's head with his sword. Gunnlaugr killed Hrafn, but Gunnlaugr eventually died from his head wound. To repay Hrafn's cowardly betrayal, Gunnlaug's father, Illugi, killed and mutilated a number of Hrafn's relatives.

|

The stories say that fighters sometimes swapped weapons from one hand to another. In chapter 10 of Droplaugarsona saga, it is said that Helgi showed his skill in arms in a fight against Hjarrandi. Helgi threw up his sword and shield and caught them in the opposite hands, which allowed him to strike a blow against Hjarrandi's thigh. The move would seem to be very risky, yet Helgi was considered to be one of the three best fighters in Iceland (Eyrbyggja saga, ch.12). Perhaps only someone as skilled as Helgi could pull this move off successfully in the chaos of battle. |

A short video demonstration of the sword and shield swap is available here in QuickTime or Windows Media format. |

|

The sagas say that occasionally the pommel was used to strike a blow. Typically, the blows were not meant to be lethal, but rather were intended to humiliate. In chapter 82 of Grettis saga, Ůorbj÷rn woke up Glaumr by hitting him on the ear with his pommel. In chapter 10 of HŠnsna-١ris saga, Ůorkell told a farm hand to do his bidding, or else he'd plant his sword pommel in the man's nose. |

|

It's not clear how boys trained to learn the use of weapons. A few wooden swords and fragments have been found, some of which represent faithful copies of real weapons, but we don't know if they were toys or serious practice weapons. Nor is it clear at what age boys started training. It has been suggested that as soon as boys were able to stand and grasp objects, wooden toy swords were put in their hands. Perhaps the first steps in teaching the use of weapons began with boys as young as three years old. Archaeological evidence suggests that even young boys had exposure to and skill with weapons. |

|

|

A number of child-size iron weapons have been found in children's graves. The sword, spearhead, and axehead shown to the left were found in a child's grave in Norway, along with a similarly sized shield boss. The sword, probably cut down from a full-sized sword, is only 39cm long (15in). The hilt suggests a date in the first half of the 10th century. A modern reproduction of the child's axe is shown to the right. Although small, it's still a formidable weapon. |

|

Similarly, a child's size axe was found in the grave of a 10 year old boy at Straumur in Iceland. The axe head is 5cm (2in.) long. We don't know if these were training weapons, or weapons meant for use in earnest combat by children, or simply tokens of the family's wealth.

The evidence from the sagas is contradictory. One episode suggests children were not capable of wielding adult-sized weapons. In chapter 11 of FljˇtsdŠla saga, Helgi and GrÝmr Droplaugarson, aged twelve and ten years, left their home one night in order to kill ŮorgrÝmr tordřfill (dungbeetle) for his slander. The boys carried their usual thonged-spears (snŠrisspjˇt), but they did not carry their late father's sword because neither had the strength to carry it.

|

Other saga evidence suggests that young boys did use weapons to kill, notably chapter 40 of Egils saga SkallagrÝmssonar. Young Egill used an axe to kill a player on an opposing team in a ball game in retaliation for some rough treatment in the game played at HvÝtarvellir (right). Egill was six years old. The deed is quite believable if young Egill used an axe similar to the one shown just above. |

|

There are examples that suggest that boys were "excused" from combat. They were not expected to participate, and they were shielded from it. In chapter 14 of Hrafnkels saga, Hrafnkel and his men attacked Eyvindr and his party. The boy traveling with Eyvindr did not participate because he didn't think he was strong enough. After the fight began, he was free to ride away on his horse.

|

In chapter 44 of Eyrbyggja saga, the story of the fight in the hayfield at Kßrsstair is told (left, as the farm appears today). After Snorri goi broke up the fight, he allowed Stein■ˇrr and his men to ride away without being followed. Subsequently, it was discovered that Snorri's son ١roddr had been seriously wounded by Stein■ˇrr. The boy was twelve years old. Snorri immediately gathered his men to chase after Stein■ˇrr in order to repay him for his shameful act. |

Other episodes in the sagas suggest that boys did participate in killings, particularly for revenge. There is the example in chapter 11 of FljˇtsdŠla saga described above, where the sons of Droplaug killed ŮorgrÝmr tordřfill. Another example is related in chapter 14 of Hßvarar saga ═sfiring. Ůorsteinn and GrÝmr, 12 and 10 years old, attacked and killed the powerful Hˇlmg÷ngu-Ljˇtr (Ljot the dueler) to avenge the harsh treatment the boys' father received at Ljˇt's hands.

In chapter 42 of VatnsdŠla saga, ŮorgrÝmr, the father of the 12 year old boy Ůorkell krafla, made a deal with his illegitimate son. If the boy were to bury an axe in the head of Ůorkell silfri, one of ŮorgrÝm's rivals, the boy could keep the axe, and ŮorgrÝmr would acknowledge the boy as his son. The boy kept his side of the bargain, and after the killing, he said that it was not too much work to acquire the axe.

The stories suggest that Norse people were familiar with the concept of "mock" combat, called skylming. It's not clear whether this "fencing" was sport or practice, or perhaps both. In chapter 12 of Gunnlaugs saga ormstunga, Gunnlaugr came upon two men fencing who were surrounded by many spectators. Gunnlaugr walked away in silence when he realized they mocked him as they fought.

The sagas occasionally mention berserks, warriors with exceptional ferocity and strength, some having supernatural powers. But the sagas don't seem to agree on just what made someone a berserk. It's not clear that the word (berserkr) had a consistent meaning in the saga age.

Some berserks were valiant warriors, the vanguard of the king's fighters and were admired. Others seem to have been thoroughly evil men, roaming the countryside challenging weaker men to duels, with their wealth and their women at stake. Others were cowards and bullies, unable to fight effectively at all. In some cases, the word was applied to any hard fighter. Perhaps the word had multiple meanings in the saga age.

The berserks who served the king of Norway defended the bow of the ship. Chapter 9 of VatnsdŠla saga says that they used wolf-skin cloaks (vargstakkr) as their mail shirts (brynja), and so they were called Wolf-Skins (˙lfhÚinn). They fought ferociously for the king.

|

Other berserks could enter a trance-like rage, exhibiting extraordinary strength. Once in this frenzied state, they were not like human beings, but more like animals. They howled like wild animals, and they bit the edge of their shields. The image of a berserk biting his shield has been preserved in a 12th century chess piece (right). These beserks had no fear of fire or iron. Swords would not bite them, and they could walk through fire without being burned. A berserk could blunt his opponent's weapon by looking at it. They were shape-changers, taking on characteristics of wild animals. When they charged, they were unstoppable. But when the frenzy wore off, they were exhausted and powerless and had to lie down and rest. Chapter 6 of Ynglinga saga says that these skills were first taught to men by Ëinn, the highest of the gods. Some modern scholars have suggested that berserks used medicinal herbs (such as mushrooms) or other drugs to enter their trance state. To my knowledge, there is little in the sagas, or in other sources, to suggest that foreign materials were needed to bring on this frenzied state. The etymology of the word berserkr is greatly debated. Some have suggested the word derives from "bare shirted", since berserks went into battle without mail, and thus bare of any armor. Others suggest an older German derivation meaning "bear shirt", since these men wore the skins of animals, which could have included bear skins. Both suggestions would seem to have problems. |

|

|

In the sagas, berserks sometimes appear as stock characters. They are suitable villains for the saga hero to vanquish. Chapter 25 of Eyrbyggja saga tells the story of Halli and Leiknir, two berserks who were given to Styr. At first, Styr was able to put them to good use against his enemies, but later, the berserks became troublesome. In chapter 28, Halli asked for the hand of Styr's daughter in marriage, which would have been a disgrace for Styr's family. Styr went to Snorri goi for advice, who devised a plan. Styr told the berserks that they must prove themselves worthy of the marriage by building a road through an impassible lava field. When they finished the arduous task, Styr invited the berserks to take a hot bath and to rest. Styr locked them in the bath-house, and then made the house unbearably hot. As the berserks broke down the door and burst out, Styr killed them with a spear. He buried them in a deep hole alongside the path through the lava. The grave mound is still visible along the path (left), and when it was investigated, the mound was found to contain the bones of two very large men. |

Some berserks seem to have been merely incompetent. Bj÷rn jßrnhaus (iron-skull) was a great bully who came to a house where Gl˙mur was a guest, as is told in chapter 6 of VÝga-Gl˙ms saga. When the bully turned to insulting Gl˙mur as he sat on the bench, Gl˙mur jumped up, grabbed a burning log from the fire, and started beating Bj÷rn on the shoulders and head. Bj÷rn, stumbling and falling under the rain of blows, barely got out the door. The next day, his death was reported.

In same cases, strong fighters were called berserks, even though there is nothing in the saga to suggest that they entered a battle frenzy or took on other aspects of a berserk during their fights. Helgi Harbeinsson is called a berserk in chapter 60 of LaxdŠla saga. In the brutal fight that developed later and described in chapter 64, nothing in Helgi's actions suggests a berserk frenzy.

Not everyone in the sagas is depicted as being skilled with arms. In chapter 24 of Finnboga saga ramma, Uxi struck at Finnbogi three times with a two-handed axe, and three times failed to connect. In chapter 24 of Bjarnar saga HÝtdŠlakappa, ١rr sent the brothers Beinir and H÷gni armed with axes to kill Bj÷rn at his home at Hˇlmur, on the shore of HÝtarvatn (right). When they made their attack, Bj÷rn used no weapons on the brothers, but he was able to grapple with them and bind their hands behind their backs. Bj÷rn then stuck their axes under their bonds in back and sent the brothers back to ١rr, thoroughly humiliated. |

|

Nor is everyone in the sagas depicted as being courageous in their use of weapons. In chapter 39 of Harar saga og Hˇlmverja, ١rˇlfr entered Ref's house at night to kill him. As ١rˇlfr waited outside Ref's bed-closet in the dark, his nerve failed him. Ref's mother, Ůorbj÷rg, saw the killer and shouted a warning. Ůorbj÷rg grabbed ١rˇlfr, got him underneath her, and killed him by biting through his throat.

A speculative reconstruction of the fighting moves of a man who attacks strongly, but who becomes timid when he realizes his opponent is strong, is shown in this Viking combat demonstration video, part of a longer fight.

Men were not above using dirty tricks to gain the advantage in a fight. In chapter 23 of FˇstbrŠra saga, Falgeirr and Ůormˇr were fighting on a cliff above the sea. Both had been severely wounded, and both were exhausted. While grappling, they fell into the sea. In the water, Ůormˇr pulled down Falgeir's trousers so he couldn't swim, and Falgeirr drowned.

|

|

<< Previous article |

Back to Arms and Armor |

Next article >> |

|

ę1999-2025 William R. Short |