|

|

Historical Sources

Our knowledge of the Viking age comes primarily from two kinds of sources: literary materials and archaeological finds.

|

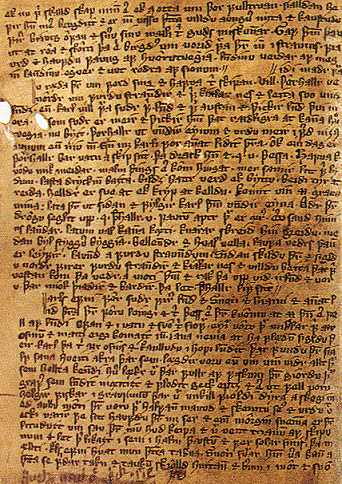

Literary Sources. In the past, literary sources were the chief source of information about the Viking era. Unfortunately, very little material was actually written down during the Norse era. Despite having an alphabet and a written language, the Norse culture was primarily an oral one. The literary material composed by Norsemen was generally written down hundreds of years later, usually by someone with biases for or against the material being transcribed. For example, the 13th century writers were generally Christian, writing about the activities of their 10th century heathen forebears. On one hand, they may have wished to glorify their ancestors' deeds while, on the other hand, downplaying their paganism. In addition, the manuscripts that survive today are copies of copies, likely to contain scribal errors and emendations. Thus literary sources can not be accepted without reservation. For reasons not well understood, the Icelanders were the writers, poets, and historians of the Norse world. It is their writing that dominates the literature of this age. They wrote in a variety of styles: historical novels (the Íslendingasögur), history texts (Heimskringla), mythological poems (Edda), romances (riddarasögur), legendary stories (fornaldarsögur), textbooks (Grammatical Treatises) and others. Although these books were written one hundred years or more after the close of the Viking age, they provide some of our best views of that era. Books such as Landnámabók provide information on the genealogy and history of the original settlers in Iceland, and their descendants. Law books, such as Grágás, contain traditional laws which date from the Viking age and can be used to provide more information about the society at that time. |

|

Skaldic poetry is probably the best preserved contemporary material from the Viking age. It represents an oral tradition that was passed from generation to generation reliably, due to the meter and rhyme which served to catch errors before they propagated. Even though these poems were not written down until centuries later, they were probably written down accurately, and thus they provide a contemporary view of the people, events, and cultural outlook of the Norse people.

More information about Norse literary sources is available in the article on Norse Literature, and an article about using the sagas as a historical source is available in the Hurstwic library.

Contemporary authors from outside Norse lands also wrote about the Norsemen, and a few of their works still survive. Some of the authors were trading partners with the Norse, such as the Arabs. Ibn Fadlan's first-hand account of the funeral ceremony of a Rus chieftain (thought to be Viking traders in Russia) is perhaps one of the better known examples, although some of the details are so fantastic that they are hard to accept literally.

However, most of the surviving contemporary material was written in Latin by foreign clerics who probably had not visited the lands they wrote about. Adam of Bremen's 11th century writings contain interesting descriptions of Norse lands not found elsewhere in contemporary writings.

Other contemporary accounts survive, but generally, they focus on the more dramatic and violent aspects of the Norsemen: the raids, the plunder, the slaughter, and the battles. This focus is understandable, since the clerics who wrote this material were often the victims of the Viking raids.

As fascinating and entertaining as the literary sources are, they must be used as historical references with caution and with an understanding of who wrote them, when they were written, and for whom they were composed.

|

Archaeological sources. As the 20th century progressed, more and more of our knowledge about the lives of the Norsemen came from the work of archaeologists. The literary material has been overtaken by archaeological material as the dominant source of evidence. Sometimes, the interpretation of archaeological finds is relatively straight-forward, especially when the artifacts are well-preserved, complete, and undisturbed. The photo to the right shows an excavation at Reykjaholt, the 13th century farm of Snorri Sturlason. The site is interesting not only because Snorri lived here, but because it also was one of the first farms in Iceland. It has been continuously occupied from the 9th century to the present. |

|

When I visited in 1998, I was told that excavations had only reached the level of the 19th century. A subsequent written report indicated that a portion of the tunnel leading from Snorralaug (Snorri's bath) to his farm house had been uncovered and studied.

But more usually, the evidence is not so easily interpreted. Usually, only a fragment, or the shadow of a fragment, remains after centuries under the ground or under the water. For example, the support posts from a wooden building may survive only as dark spots in the soil. Multi-disciplinary approaches to the analysis and interpretation of finds has greatly increased the information that can be extracted from an object.

|

For example, the technique of dendrochronology (the dating of wooden objects by correlating the pattern of the tree rings in the object with known historical patterns) has allowed precise dating of a variety of important finds from Norse lands. In some serendipitous cases, it has even permitted the origin of a wooden artifact to be determined, as in the case of a Baltic area find that matched no other tree ring patterns except those from Ireland. Even thin planks can be readily dated, since the riving method used to create planks in the Viking age preserves nearly the full ring pattern of the original log. |

|

|

Studies of skeletal remains provide important clues to the health of the person during his or her lifetime, including injuries or diseases that may have been suffered. The photo to the left shows the in-situ skeletal remains of a child from a Christian burial in Iceland's early history, excavated on the day I visited the site. |

|

The volcanic activity in Iceland provides archaeologists with an important tool for dating finds, called tephrochronology. The tephra layers in the soil (right) laid down from the ash and other solid materials from volcanic eruptions can be distinguished from one another and so can frequently be used to date a find. By studying the position of the find relative to the individual layers of tephra in the soil, it becomes possible to say (for example) that a structure was built after the Hekla eruption of 1104, but before the Hekla eruption of 1158, and not rebuilt afterwards. Additionally, the tephra layers in the turf blocks (left) used to build turf houses can be used to date the cutting of the turf, and thus date repairs and modifications to the house. |

|

|

The dates of a few of the tephra layers in a soil sample from south Iceland are indicated in the photo to the right.

|

|

The work of archaeologists is made more difficult by the fact that few objects are intentionally buried. Finds such as grave goods, silver hoards, or ships intentionally scuttled fall into this category. But most archaeological finds are discarded items, thrown in a jumble on the midden heap when they have no further value. This muddle further complicates the task of forming a coherent picture of life in Norse times from archaeological finds.

Fortunately, new finds are being discovered and excavated, and new techniques are being brought into play, increasing our knowledge of this era. No better example can be found than the report of the excavations at Hofstađir in north Iceland published by Fornleifastofnun Íslands in 2010. New techniques and new approaches allowed a significantly deeper and broader understanding of the lives of the people who inhabited this important Viking-age longhouse in the 10th century.

|

|

©1999-2025 William R. Short |