|

|

Turf Houses in the Viking Age

The photos on this page were taken at three different turf house reconstructions:

at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada;

at Şjóğveldisbær in Þjórsárdalur, Iceland;

and at Eiríksstağir in Haukadalur, Iceland.

|

The Şjóğveldisbær longhouse (located in Þjórsárdalur) is a re-creation of a typical Icelandic turf house from the end of the Norse era and is based on the house at Stöng, a short distance away that was covered with ash during a volcanic eruption of Hekla in 1104. As a result, the ruins were better preserved, with more physical evidence extant, than other Norse era longhouses. The excavated ruins (right) are enclosed within a modern building, protecting the site from further deterioration. |

|

The Stöng farm was large and rich, and after the eruption, it may not have been abandoned completely until the climate changes that occurred in the 13th century. During its prosperous years, perhaps twenty or more people lived in this longhouse. The re-construction is operated by Şjóğminjasafn Íslands, the Icelandic National Museum, and Landsvirkjun, the electrical generation and distribution company of Iceland.

|

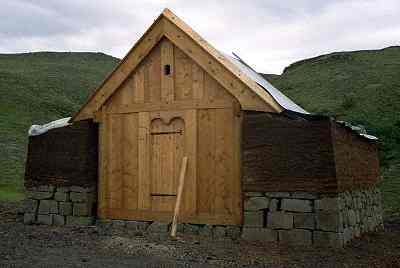

Eiríksstağir was the farm of Eiríkur rauği (Erik the red), who later settled Greenland. His son, Leifur Eiríksson, who led one of the voyages to Vínland, was born on this farm. The re-construction is based on the ruins located a short distance away, further up the hill (visible only as a depression in the foreground of the photo, with the reconstructed house in the background). While it was occupied, the farm was only a modest operation. The archaeological study of the ruins suggests that the house was modified at least once while occupied, both to expand it, and also to repair damage that may have been caused by a landslide from further up the hill. |

|

The L'Anse aux Meadows site was probably a way station for Norse exploration in North America one thousand years ago. The longhouse re-construction is operated by Parks Canada and is based on archaeological findings at L'Anse aux Meadows, and elsewhere. The original longhouse on the site may have been constructed by Leifur Eiríksson and the other members of his party. The reconstruction is based on Hall A, which includes not only living quarters, but also work rooms for the crew. |

|

The illustration shows the floor plans of the excavated ruins of the 3 Viking-age turfhouses mentioned above, in addition to two other houses that have not been reconstructed, but which represent the two extremes of turfhouse size: Ağalstræti 14-16, a small and early turfhouse found in Reykjavík (and named for the street address where it was found), and Hofstağir, a grand home for a chieftain in the 10th century, found in north Iceland.

The houses are similar in overall construction, but differ remarkably in details, primarily because the houses were built for different purposes, at different times in the Viking age, by families with differing resources. The Stöng farmhouse is based on a permanent, continuously occupied structure built late in the Norse era and owned by a wealthy family. In contrast, the L'Anse aux Meadows site was temporary, a simple way station and ship repair site built in the middle of the Norse era. So, for example, the Stöng house has wood wainscoting on the interior walls, to cover up the turf, while the L'Anse aux Meadows has no such frills. The Eiríksstağir house falls somewhere in the middle: it's a permanent structure, but built by a family of more modest means. Ağalstræti 14-16 may be one of the first turfhouses build in Iceland and contains features not seen in later turfhouses, as discussed later in this article. Hofstağir is a large, imposing house and was probably used for feasting and cult practices in the presence of large numbers of guests.

Some of the differences between the houses result from

differences in interpretation of the same physical evidence. Various scholars may look at the same archaeological evidence and draw

very different conclusions. The Norse did not leave behind any plans, and the interpretation of the physical remains is difficult.

|

The house begins with the construction of stone footings. Besides forming a firm base on which the house rests, they also keep the wooden structural elements of the house away from the soil, protecting them from rot. The footings of the house at Stöng are shown to the right. |

|

|

|

The L'Anse aux Meadows house, being a temporary structure, had very limited footings. In most places, the wood supports rested directly on the soil, which would have resulted in the wood rotting out fairly quickly. The stone footings are typically the only part of Norse era turf houses that remain visible today. The photo to the left shows the footings of turf houses on the site of the first settlers on the island of Heimaey in Iceland. |

|

The structural support for the house was provided by wooden interior posts and beams (rather than by the walls, which supported essentially no weight). The wooden beams locked together using pegs and notches (right), rather than iron nails. The main structural elements are shown in the sketch to the left. |

|

|

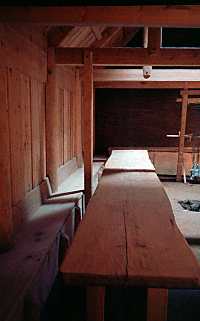

Pillars, resting on stones on the floor (left), rise to support two long rafter-bracing roof beams, which run the length of the house (right, at Stöng). At each pair of pillars, the roof beams are tied together with a cross beam. Rising from the middle of the cross beam is a short pillar which supports the long roof ridge beam. The upper rafters form a strong triangular structure with the rafter-bracing roof beams and the roof ridge beam, and the weight of the upper roof is carried by the pillars to the floor. Lower rafters (hidden behind wainscoting in the photo to the right) carry the weight of the lower roof to another set of shorter vertical pillars set just inside the turf walls at the back of the benches. The pillars are located in the airspace (skot) that separates the turf walls from the wooden wainscoting. The airspace helps to insulate the house, and it protects the wood from dampness and rot. While not normally used by the inhabitants of the house, this airspace was apparently large enough that people could pass through it. Şorkell made his escape through the airspace of the house after killing Glæğir in chapter 44 of Vatnsdæla saga. In chapter 27 of Reykdæla saga og Víga-Skúta, Skúta discovered two assassins who were hiding in the airspace waiting for an opportunity to attack. |

|

|

Although it's not emphasized in either the photo or the sketch above, the upper and lower rafters are often separate timbers which meet at an angle, rather than straight-on. The angle helps resist the load of the roof, and it allows the rafters to be made from two timbers, rather than one, long straight one. That was an important consideration in lands like Iceland, where timber resources were limited. In such places, either the thin trunks of native trees, or driftwood found on the shore (right) was commonly used for house construction. The only alternative was to import timbers from overseas. |

|

Stories tell about the öndvegissúlur (high-seat pillars) and how the early settlers of Iceland used their high-seat pillars to interpret the wishes of the gods in deciding where to settle. Although it's not clear what the high-seat pillars were, most likely they were the main support pillars of the house that framed the high-seat (öndvegi), the most honorable place on the benches, which was occupied by the head of the household.

Some houses contain objects placed under structural elements, which have been interpreted as cult offerings. Tiny sheets of embossed gold foil have been found under the support posts in the location of the high-seat pillars, as described in the Hurstwic article on Viking religious practices. The early longhouse at Ağalstræti 14-16 had animal bones intentionally buried under the foundation of the back (western) wall, perhaps placed there as offerings.

|

For the walls, turf blocks (left) were used, approximately 15 to 20cm thick by about 50cm by 1.5m. (8 inches by 20 inches by 60 inches). |

|

Long strips of turf were cut with turf knives (the scythe-like blade in the photo to the right), and the sods of turf were peeled off the ground. Smaller turf blocks were cut with a rutter (shown in photos both left and right), a small spade having a spike protruding outward at the top of the blade. The spike allowed the spade to be driven into the turf with the foot. The best turf for house construction was about 60% vegetable matter, primarily the roots of the plants growing in the bog, and 40% mineral, the sandy material in which the plants grew. When cut, the turf was saturated with water. After cutting, the turf was set aside to allow it to dry out before being used. When dry, the turf is lighter than one might expect and has a consistency a bit like cork. |

|

|

During construction, two separate courses of these turf "bricks" are laid, creating a central cavity that is filled with gravel or dirt. At regular intervals, turf stringers were placed across the two courses to tie them together and providing greater strength to the wall. The finished wall is about 2 meters thick (7 feet), with the gravel core providing drainage. When I visited Stöng in the summer of 1998, one of the walls was being rebuilt (left), allowing a clear view of the wall construction. (A staff member at the National Museum, which helps run the farmhouse at Stöng, told me that the cost of upkeep on the turf house has exceeded everyone's expectations, and has been a real budget buster.) |

|

A few of the turf walls in the Stöng reconstruction use the klömbruhnaus technique (right), resulting in a herringbone pattern in the turf. The evidence for this construction style is slight for the Norse era, but it was commonly used in later eras. Triangular shaped pieces of turf are laid on their side to create a wall using the klömbruhnaus technique (left). The details were visible when some of the walls at Stöng were re-built in 2011. |

|

|

The roof is made of a layer of small tree branches laid over the main support rafters (seen from the inside at Stöng in the photo on the left). Over this goes a layer of turf (which can be seen from below in the photo). Ideally, a layer of birch bark is placed on top of this (for water proofing) and another layer of turf. The branches allow air to circulate between the turf and wooden rafters, helping to prevent rot. |

|

Finally, the roof is topped with a layer of living grass sod (right). The roots of the grass grow into a web that ties the structure together. Most rain runs off the grass and down into the gravel core of the wall to drain. Wood-lined smoke holes dot the roof of the house, above each of the fireplaces. They allow smoke to escape from the interior, and they were probably the only way exterior light could get into the house, although it has been suggested that a row of small holes at the base of the roof also permitted light to enter. The sagas talk of a skjár, an opening in the wall covered with a removable screen, probably a translucent animal membrane. The opening would have allowed light to enter, and smoke to exit. In Gull-Şóris saga (ch. 13), Şorbjörn escaped from his house while under attack by putting a log under the skjár and climbing through it, taking the log with him so his enemy couldn't follow, which tells us something about the height of the opening above the floor. However, the details of how such an opening could be constructed through the double walls of turf remain puzzling. Saga evidence suggests that roofs could be peeled off, either by a strong gust of wind (Gísla saga chapter 13), or by an attacker intent on entering a locked house (Eyrbyggja saga chapter 26), or occasionally by supernatural creatures (Grettis saga chapter 32). |

|

|

Other than the smoke holes, the only exterior use of wood was the front entrance and door, which was sometimes elaborately carved. The photo of the door at Stöng (left) shows another exterior feature of turf houses: an entrance area paved with stones outside the door, which keeps that area from turning into a mud pit due to the heavy foot traffic. At Eiríksstağir (right), there are two such paved areas in front of the house, convincing evidence that the door was moved at some point while the house was occupied. |

|

|

The front door at the house at Eiríksstağir (left) shows the keyhole in the center of the door, and the protruding tab for operating the sliding locking mechanism just above it to the right. |

|

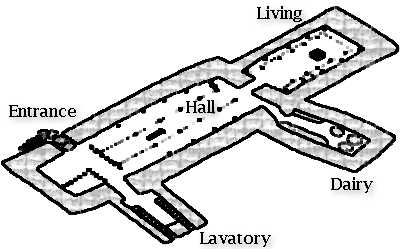

Inside, longhouses were typically divided into several rooms along their length by turf or wooden walls. At Eiríksstağir, there were three rooms in the house, shown in plan to the left. At the east end, there was a small entrance and storage area, with an exterior door on the south side. Note how thick the turf walls are (the stippled area) relative to the size of the rooms; a substantial portion of the footprint of the house is taken up by the exterior walls. At the entrance, a door on each side of the wall helped to secure the house, to keep out the weather, and to prevent drafts. |

|

At the west end was the pantry, with an exterior door on the north side (right). The archaeological evidence for this door is less clear. The door would have reduced foot traffic through the narrow hall carrying food and supplies to the pantry, but because the hill slopes steeply down to the house on the north side, this area must have stayed filled with snow every winter (left), blocking the door. |

|

|

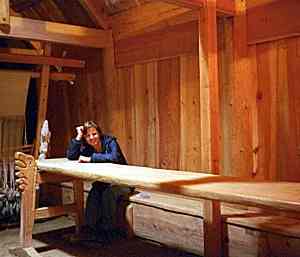

The main hall in the middle of the house took up most of the floor area, with a fire pit in the middle. Benches lined both sides of this room. |

|

|

Benches on one side (left) were open, and used for sitting, working, eating, cooking. Tools, storage chests, tables, and the loom were on this bench. Benches on the other side (right) were partitioned, and served as beds. Surviving beds, benches, and other sleeping areas are very small. It has been suggested that people slept sitting up in the Viking age, with their backs against a wall or partition, or even against their shields. |

|

|

An illustration from a later medieval manuscript (from after the end of the Viking age) shows how this might have been done. It shows a man sleeping in bed, his head and upper body propped up against the wall. His shoes and leg-wraps are neatly placed under the bed. On the floor, a servant or slave sleeps, likewise, propped up against a pillar. A loft over the pantry at Eiríksstağir was used for food storage, and a loft over the entrance was used for sleeping. It is thought that slaves and children slept in the loft. |

|

At Stöng, a more prosperous farm, the floor plan was more elaborate. In addition to the main rooms of the house, two additional rooms were stuck onto the back of the main building. The floor plan at Stöng is shown to the right. The locations of the support columns and the extent of the benches is indicated in the plan, as well as the location of the firepits for the two rooms. The house was 28m (92 ft) long. |

|

|

The room furthest from the entrance was the stofa, the main living room (left). The saga literature mentions that women congregated in a specific part of the house reserved for their exclusive use during the day, where they did their daily chores (and, according to the stories, swapped gossip). At Stöng, this room was probably that place. The loom was located here, along with tables and sitting-benches, which are shallower and higher off the floor than the multi-purpose benches in the main room. The space under the benches may have been used for storing textiles as they came off the loom. These benches were suitable for eating, socializing, and a variety of tasks. |

|

The benches and tables would have made this room a fine place for feasting, especially since the pillars are set back closer to the wall, creating a wider open space down the middle of the room than that of the hall. The sagas suggest that in some cases, there were cushions on the bench on which people sat (Eyrbyggja saga chapter 20). |

|

|

The hall (skáli) was the main room of the house (right). Daily indoor work was performed here. Food was prepared on the fire in this room. This room also held the quern, used for grinding flour. |

|

At night, this room was the sleeping quarters for everyone on the farm, so the benches here are lower and deeper, more suitable for sleeping. It also has a bed closet, a small, closet sized enclosure with a door, located on top of the bench. The open double door to the closet is visible to the rear in the photo. |

|

|

A bed was located in this closet for the master of the farm and his wife. The depth of the closet is the same as the depth of the bench, and the width is no greater than the depth, so the closet is quite small. The bed takes up the entire space within the closet. At night, the doors to the closet were closed and bolted from the inside, providing the master of the house and his wife with additional security against intruders. |

|

|

The rest of the inhabitants of the house slept together on the benches on either side of the hall. |

|

Two additional side rooms were tacked on to the back of the house, possibly later additions made after the house had been built and occupied for a time. |

|

|

One of the side rooms was used for dairy storage (left). Large wooden vats, partially set into the earth, were found here. By being partially below ground, the contents of the vats would be kept cool. Additional insulation was provided in this room by stones placed between the rafters and the roof (right). The vats held dairy products, such as skyr, and they may have held meat pickled in sour whey. The vats are over 1.4m in diameter (55in) and so could hold a substantial quantity of foodstuffs. |

|

|

More puzzling is the other side room, with its stone trenches set in the floor (right). The trenches pass through the rear wall of the room to the outside of the house. It seems likely that this room was a latrine. The trenches served as gutters to carry wastes out of the house. It's quite possible that wooden benches with holes cut in them were set over the trenches on which people sat. |

|

|

It's also possible that a simple wooden pole (stöng) was placed above the trenches on which people sat. Stone slabs set into the floor on either end of the trenches (left and right) in the Stöng farmhouse ruins have notches cut out of them that would nicely hold a pole in such a position. |

|

|

When the saga literature describes someone relieving himself, that person does so outdoors, or in an outbuilding. For instance, in chapter 47 of Læxdala saga, it is said that at the time of the saga (10th century), it was fashionable to have outdoor toilets some distance from the farmhouse. In addition, it seems unlikely, based on the archaeological remains, that a house like Eiríksstağir (right, built in the 10th century) had an indoor lavatory. |

|

The 10th century farm at Hofstağir in north Iceland had a lavatory in a separate structure a short distance from the longhouse. As at Stöng, a stone-lined trench carried wastes out of the building. Traces of human feces found in the trench make it clear that this structure was a latrine. The building had space for three (and possibly more) people to sit over the trench.

On the other hand, episodes in the sagas show the advantage of an indoor lavatory. Attacks could be made on men making an nighttime visit to an outhouse, such as the attack on Snorri goği described in chapter 26 of Eyrbyggja saga. It's possible that by the time Stöng was built, late in the Viking era, indoor lavatories were more common.

The lavatory at Stöng seems to be an enormous structure for its intended purpose. It almost appears big enough to have permitted every member of the Stöng household to relieve themselves simultaneously. While I make the statement in jest, the sagas suggest that, in fact, groups of men did socialize while in the privy. Chapter 25 of Flóamanna saga says that while some men were sitting in the privy, others stood nearby, and they all talked and compared their accomplishments. The privy might have been a good place to hold a private conversation, something that would have been impossible in the open longhouse.

It's even been suggested that the farm at Stöng took its name from the long poles (stöng) used as seats in its fine and imposing lavatory.

|

The open area (anddyri) between the exterior door and lavatory was probably the Norse equivalent of a mudroom, where wet or dirty outer garments were removed before entering the living areas. Farm equipment and tools may have been stored in this area, as well. At the Eiríksstağir longhouse reconstruction, farm tools, horsehair ropes (left) and pack saddles (right) are stored in the anddyri. In chapter 44 of Vatnsdæla saga, Glæğir took his bath in the anddyri. At Stöng, there is a small chamber in this room, which was probably used for food storage, such as dried fish, smoked meat, and cereal grains. |

|

|

A wall and door (left) between this entrance room and the main hall kept drafts from the outside from reaching the living quarters. Most of the interior doors and passageways at Stöng are low and narrow, requiring one to bend over to pass through. The photo to the right shows the passageway between stofa and skáli. The thickness of the interior turf wall is quite apparent in the photo. |

|

The sagas tell of hidden rooms and secret passages in some longhouses (although there is no evidence for such structures at Stöng). In chapter 28 of Reykdæla saga og Víga-Skútu, Skúta's bed closet is described having a trap door connecting to a tunnel which led outside the house to the sheep-barn. Above the bed was a kettle and a set of pot-chains arranged to fall into the kettle and awaken Skúta should an intruder enter the bed closet.

|

In addition to the longhouse, the original Stöng site had a smithy (left), animal sheds (right), and other out buildings, which have not been reconstructed. Other out buildings that have been found at Viking-age house sites include specialized buildings, such as work houses, smoke houses, bake houses, and brew houses. |

|

|

Recently, a firepit was found (partially excavated in the photo to the left) in the outbuilding of a Viking-age house site. The firepit is more than 3 sq meters (32 sq ft) in area, suggesting that prodigious amounts of cooking and heating took place on the site. |

|

In the early part of the Viking age, it appears that everything was contained in the longhouse: animals, people, tools, food storage, work shop. Later, all but the people were moved to out buildings. While this arrangement was common in early longhouses found in Norway, only one example has been found to date in Iceland: at the longhouse at Ağalstræti 14-16 in Reykjavík. There are far too few stalls to have housed all the valuable livestock on a farm of this size. Perhaps only the most prestigious animals were kept here, such as plow oxen, or valuable horses, in order to show them off to visitors. |

|

|

One type of outbuilding often found is the sunken-floor hut (also called pit-houses), which were half buried in the ground. I came upon a small, modern pit-house (left) on a beach in Iceland. It has been suggested that these buildings might have been the first to be constructed by settlers at a new home site. Such buildings would have gone up quickly, allowing families to have at least minimal shelter while the more comfortable longhouse was under construction. After moving into the longhouse, the hut may have been used for some other purpose, or simply allowed to collapse. |

A number of uses for these houses have been suggested. Archaeological evidence at several excavated house sites suggests they were used for sewing and weaving, and may have been dyngja: rooms where women gathered to do their work that are mentioned occasionally in the sagas (for example in Brennu-Njáls saga, ch. 44).

These buildings would have been well insulated, due to their construction technique, and may have been used for storing items that needed to be kept cold. They also would have been easier to build, needing less building materials, and may have been used for housing şrælar (the slaves and bondsmen).

Some believe that these houses served as bath houses, or the northern equivalent of a sweat room, heated by fire. An intriguing suggestion is that heat generated by the fire in these small spaces might have altered the properties of the fibers or textiles, making job of creating clothing for the household easier for the women who did that work.

| Some pit-houses that have been excavated clearly were abandoned and used as refuse pits and allowed to fill with rubbish. This recently excavated pit-house (right) seems to have been intentionally abandoned and destroyed. The pit (seen in the right foreground) was filled with large stones (which have been removed and piled in the left foreground), laboriously carried from the shore of the fjord in the distance, then covered over with turf. The ritualistic destruction of the home makes one wonder if there were cult activities of some kind taking place in the house that had to be firmly put to rest. |

|

|

While I revisited the Stöng farmhouse in the summer of 1999, a new building was under construction: a church. I once again enjoyed the opportunity to take a close-up look at the internals of turf house construction. The stone footings are clearly visible, and the wooden interior. The courses of turf "bricks" were being laid when I visited, and the thickness of the walls (especially compared to the total size of the building) is evident. |

|

The completed church building is shown to the right as it looked in 2002. Obviously, only a small handful of people could fit inside the church. |

|

|

The reconstructed church at Geirsstağir (left) in east Iceland gives a clear picture of an early Viking-age church. It is thought to predate the official conversion in Iceland. Like the church at Stöng, the interior is tiny (right), with only two small side benches on which congregants could sit. |

|

|

More repairs were underway at the Stöng longhouse when I visited in 2002. The roof and walls had started to fail and were leaking. As a result, all of the turf was scheduled to be replaced during 2002-2003. The house re-construction was about 30 years old, so the deterioration of the turf occurred more quickly than anticipated. The old turf roof and walls were being stripped off layer by layer using knives (left), a very messy and muddy job. It's thought that turf longhouses had a lifetime of about 50 - 100 years in Iceland, at which point they needed to be rebuilt. Şórğar saga hreğu (ch.8) says that Şórğur built a longhouse at Flatatunga in north Iceland at the end of the 10th century that was still standing at the beginning of the 14th century. Presumably the turf had been replaced a number of times. |

|

While the work at the Stöng longhouse was in progress, sheets of plastic protected the wooden frame of the building (right) from water damage. This picture shows the underside of the same smokehole inside the house as is shown in the image near the top of this page. Once again, the construction work allowed a clear view of the wall and framing construction used for the house. As of 2004, the renovations were complete. |

|

|

During a visit in 2005, I noticed water running out from under the turf walls on the outside of the foundation. Water from the roof is supposed to run in the channel between the outer and inner turf walls and from there, directly into the ground, so finding water running on the outside was an unexpected surprise. |

|

The grass on the roof and walls is living. In times of drought, the grass is stressed, and may die off, as was the case when I visited the Stöng reconstruction in 2007 (left), and the Eiríksstağir reconstruction in 2010 (right). |

|

|

But, good weather allows for flowers and weeds to bloom on the roof, as was the case when I visited the Stöng reconstruction in 2009. |

In a new article on the importance of seating in the Viking-age longhouse, we dive deep into this topic, and into how one's seat in the house reflected one's place in society.

In summer, 2024, Hurstwic held a Fire Festival at the Viking house at Eiríksstağir where we used experimental archaeology to research the Viking-age battle tactic of burning down the house. At this time, the data analysis is incomplete, but we have issued a preliminary report video showing how the fire moves in a burning longhouse.

|

|

©1999-2026 William R. Short |

|

Visiting the reconstruction longhouses, one gets the impression that they were warm, comfortable, cozy places. That romantic view was shattered for me recently when an Icelandic acquaintance told me of his experiences as a child living in a 19th century turf house for a part of the summer each year. He said the house was damp and cold and miserable. |

|

However, Viking-age turf houses (above at Stöng) and 19th century turf houses (right at Sænautasel) were very different in design and construction. One evolved from the other, but they shared little other than that their walls and roofs were both made of turf. In many ways, the standard of living was considerably better in 10th century Iceland than in 19th century Iceland. Wood for fuel and for framing timbers was far more readily available in the 10th century, and so large rooms with high ceilings and long firepits in every room which warmed and dried the air were the rule. By the 19th century, rooms were small with low ceilings, and the heat for the entire house typically came from a single fire, usually fueled by animal dung. |

|

Now that I have spent a night in both a Viking-age turf house reconstruction, and in a 19th century turf house, I can say that I much prefer the Viking-age house.

The best we can probably say is that life in a Viking-age longhouse was not like anything that the typical reader of this page has ever experienced.